I. A Triumph Built on a Colonial Blueprint

Before we look at what happened in Kinshasa afterward, we need to be honest about the celebration itself. Every great party has someone throwing it, a guest list, and a venue. With “Beauté Congo,” the setup felt all too familiar. Strip away the contemporary packaging, and you find the same colonial structure: a European curator choosing the art, a European institution showing it, and a European audience consuming it.

Back during Belgian rule, colonial administrators like Georges Thiry would organize exhibitions where Congolese artists made the work while Europeans controlled everything else and reaped the rewards. “Beauté Congo” followed this playbook almost exactly. Want proof? Look at who owned the art. Out of 350 works celebrating a century of Congolese creativity, nearly every single piece belonged to Western collectors. The Italian-French billionaire Jean Pigozzi, who employs the curator André Magnin, provided most of the work. Only one Congolese businessman, Sindika Dokolo, had pieces in the show.

Let that sink in. An exhibition celebrating Congolese art where Congolese people owned basically none of it. When the show’s success sent prices through the roof, who made money? The European collectors who already owned everything. It was textbook cultural extraction, except this time with paintings instead of rubber.

Magnin made things worse with how he talked about it. “We thought there was no art between so-called ‘primitive’ arts and post-independence contemporary art,” he said. “I show the opposite.” Whether he meant to or not, this plays right into that tired European savior narrative. As if Congo needed a French curator to validate its own artistic continuity. It’s a view that quietly erases the violence of colonialism, treating it like some neutral backdrop where art just happened to develop.

This was the original sin of “Beauté Congo”: a triumph built on a structure that, intentionally or not, felt less like a partnership and more like a beautifully curated act of possession.

II. The Aftermath: Forging a New, Toxic Ecosystem

The market frenzy ignited by “Beauté Congo” sent a shockwave through Kinshasa. But without strong local institutions to channel its energy, the boom created a distorted and predatory new ecosystem. In this new reality, the artists who thrive are not necessarily the most original, but the best connected and most efficient at producing what the market wants. This system is propped up by three pillars: the art factory, the plagiarism epidemic, and the gatekeeping families.

From Artist’s Studio to Art Factory

Some of the celebrated artists from the exhibition are now brands. Their studios have transformed into ateliers that function less like places of creation and more like the workshops of luxury fashion houses. Talented street children are brought in to learn the trade, but their primary job is to produce work in the style of the master. The individual artist has become a logo.

“Papa Fame” is no longer an artist with a brush; he is a CEO overseeing a production line, ensuring each painting looks enough like “a real Papa Fame” before adding his signature. When you buy that painting today, who held the brush? An experienced assistant? A new apprentice? The art world doesn’t ask, treating the signature like a brand name that guarantees value, regardless of who actually did the work. Originality has been replaced by quality control.

The Plagiarism Epidemic

This factory approach, where quantity beats creativity, has created something even worse: copying has become standard practice. It’s the dirty secret everyone knows. At Kitokongo, we did our own research and found that more than 90% of certain types of paintings sold in Kinshasa galleries are straight copies. Especially those portraits of African women that tourists love. Artists just grab a photo from Pinterest, slap on a colorful patterned background, and call it original work.

The galleries know exactly what’s happening. Any decent dealer can spot a copy immediately. But they stock them anyway because plagiarists are profitable. They work fast, they work cheap, and they produce exactly the kind of exotic imagery that sells to tourists who don’t know better. Everyone wins except authentic artists, who now have to compete with a flood of stolen images. The gallery makes money, the copier gets paid, the buyer gets something to hang on their wall. It’s fraud, plain and simple.

The Gatekeepers: How Art Became a Family Business

When foreign money started flowing in, a new type of player emerged: the cultural middleman. Foreign NGOs, embassies, and foundations needed local contacts to navigate Kinshasa’s massive sprawl. Today, a small network of connected families and friend groups has cornered this market completely.

They’re the gatekeepers now. Look at who gets the grants, the residencies, the exhibitions abroad. It’s always the same names. An uncle who’s a famous artist, his cousin working as a “cultural manager” for some international organization, their childhood friend running a major gallery. They decide who gets funding, who meets the international donors, who lands opportunities. Check their Instagram and you’ll find foodie influencers traveling the world disguised as artists, posting from Venice, Dubai, Paris, everything paid for by cultural institutions.

This isn’t just nepotism. It’s a closed system where the same crew recycles every opportunity among themselves, no matter how good the competition is. Real talent sits in the shadows while these cultural brokers keep passing grants and residencies around their circle, building a wall around the art scene that’s nearly impossible to break through. They’ve turned being an artist into a members-only club, and if you’re not part of their network, you’re not getting in.

III. The Internal Rot: A Broken Local Market

It’s easy to blame foreign buyers and international markets for the distortions in our art scene. But that’s only half the story. The uncomfortable truth is that the system is so dependent on outsiders because it is completely disconnected from its own community. When artists like Rigobert Nimi ask, “For an African artist to be famous, must he necessarily pass through Europe?” the answer lies in a series of painful realities at home.

The Pricing Double Standard

There’s a self-destructive pricing strategy that’s become standard practice. Many artists operate with a mindset that goes something like this: “He’s white, so he has money. His ancestors exploited us, so I’ll charge him ten time the price.” This creates a vicious cycle. Inflated prices make the work completely unaffordable for potential local collectors, which makes artists even more desperate for foreign buyers, which reinforces the very colonial dynamic they resent. It’s a strategy for short-term cash that guarantees long-term dependence.

Cultural Investment Goes to Rumba

For decades, Congolese cultural investment and national pride have focused almost exclusively on music. Since Congolese Rumba achieved UNESCO protected status, this imbalance has only grown. The visual arts have been utterly neglected. Ironically, older artists often recall with nostalgia that the dictator Mobutu, for all his faults, was a genuine patron who loved and invested in painting and sculpture. Since his time, it has been all about the Rumba.

The Shadow of Fetishism

There are also deeper cultural barriers. For many Congolese, contemporary art is still viewed with suspicion, as something linked to fetishism or magic. A perception rooted in colonial missionary teachings that demonized traditional arts and objects. This cultural anxiety means there is very little tradition of collecting and displaying contemporary art in the home. It is something to be admired from a distance, or even feared, but not owned.

Without a campaign to educate people on the value of their own contemporary art, and without artists pricing their work for their own community, a sustainable local market cannot exist. This vacuum is the root of the problem. When a community does not value or invest in its own artists, it leaves them completely exposed to the whims, fantasies, and market demands of outsiders.

IV. The Path Forward: Prescribing the Cure

Figuring out what’s wrong is the easy part. Fixing it means sustained, collective work to rebuild our artistic ecosystem from the ground up. There’s no magic solution here, just the hard work of putting basic principles in place: fairness, transparency, integrity. These aren’t radical ideas. They’re how any healthy art market operates. It’s time we demanded the same for ourselves.

For Artists and Galleries: Rebuilding from Within

Fair Pricing Education: The destructive double-standard pricing must end. Artists need professional guidance and workshops on how to build a sustainable pricing structure that can serve both local and international clients without alienating the home market.

Gallery Accountability: Galleries are the primary engine of the plagiarism epidemic. They must face real consequences. We need a system of accountability, whether it’s a public registry of fraudulent artists and the galleries that represent them, or financial liability for selling fakes. This is basic consumer protection.

Transparent Ateliers: The factory model is likely here to stay, but it needs transparency. A painting made by an apprentice should be labeled as such. The art world needs to decide if it will treat these studios like collaborative workshops with clear attribution or continue to accept the fiction of the master’s hand.

For Institutions and Gatekeepers: Demanding Systemic Fairness

Artists’ Rights and Resale Rights: We desperately need workshops on copyright, but even more crucially, on resale rights. Did any of the artists from “Beauté Congo” receive a percentage when their works were resold for massive profits in the following years? The silence is deafening. The 4-5% resale right granted to artists in the EU must be extended to African artists whose work is sold in European markets.

Democratic Access to Funding: The family monopolies on funding must be broken. International organizations must implement open calls for grants, residencies, and projects that are widely advertised and judged by an unbiased, rotating committee. Access to opportunity should be based on talent, not bloodline.

For the Culture: Fostering Local Roots

Congolese Curatorial Leadership: The era of the European savior must end. Future international exhibitions about Congolese art must have Congolese curators, writers, and thinkers as genuine partners and leaders from conception to execution.

Cultivating Local Collectors: We must launch a sustained campaign to transform the local perception of art. This involves education in schools, community events, and a concerted effort by artists and galleries to make art accessible and desirable to the Congolese public. A strong local market is the only true vaccine against foreign market distortions.

Conclusion: The Beauty and the Ugly

“Beauté Congo” was, without question, a triumph. André Magnin assembled 350 extraordinary works and proved to the world that contemporary Congolese art deserved a place in its greatest museums. Unknown artists became international stars. Bodys Isek Kingelez finally got his due. The show forced the world to see Congolese art for what it is: a contemporary force, not some historical footnote.

The Beauty

After dissecting the system’s failures, it is essential to return to the source: the extraordinary art itself. Here are just a few of the celebrated works from “Beauté Congo,” a reminder of the genius we must fight to protect.

Pathy Tshindele

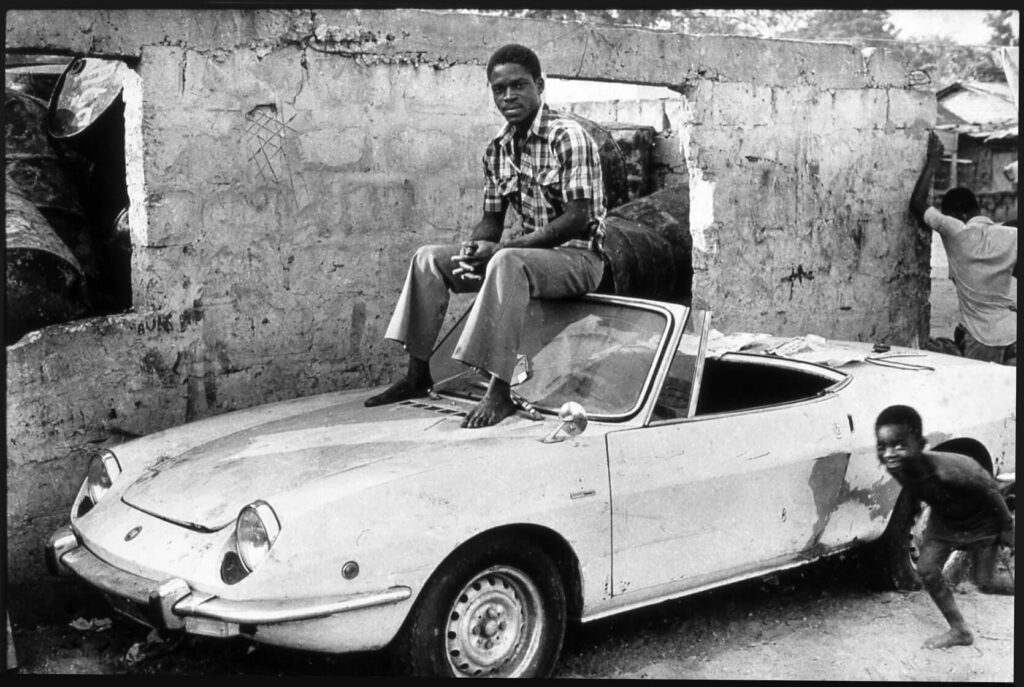

Jean Depara

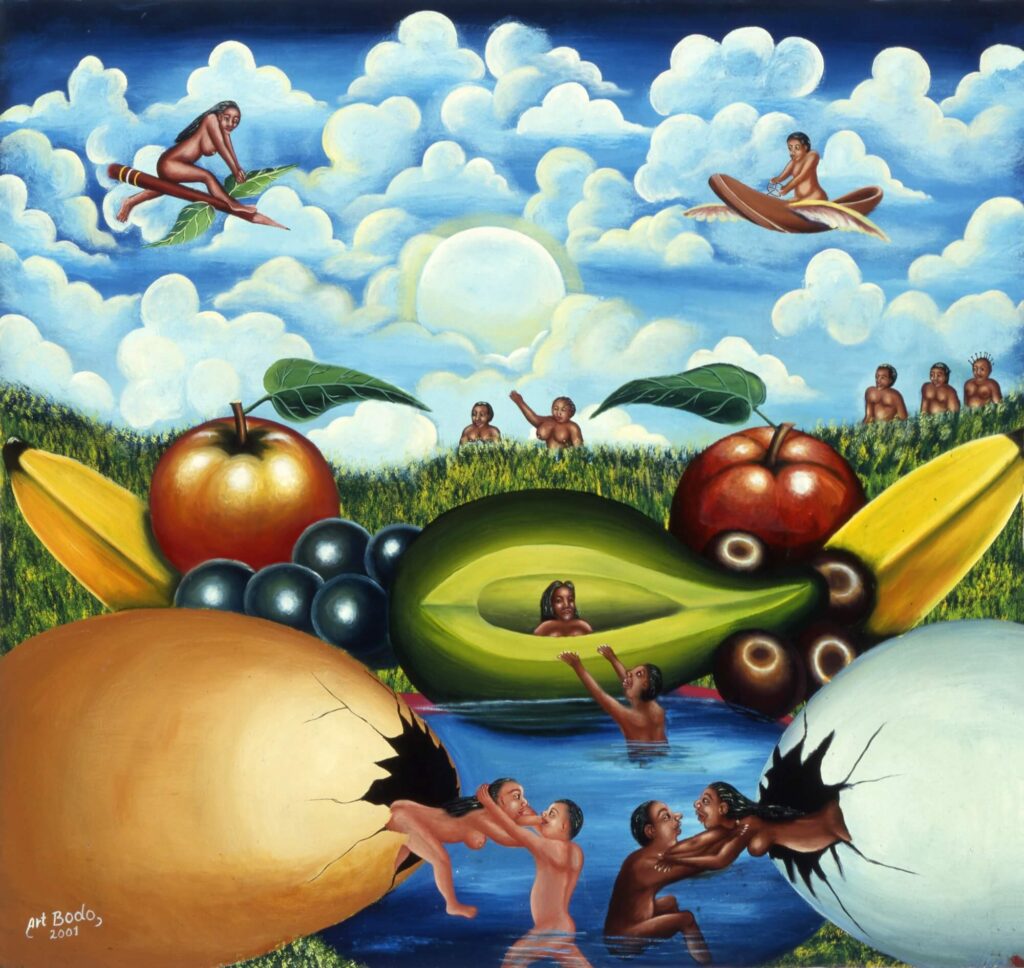

Pierre Bodo

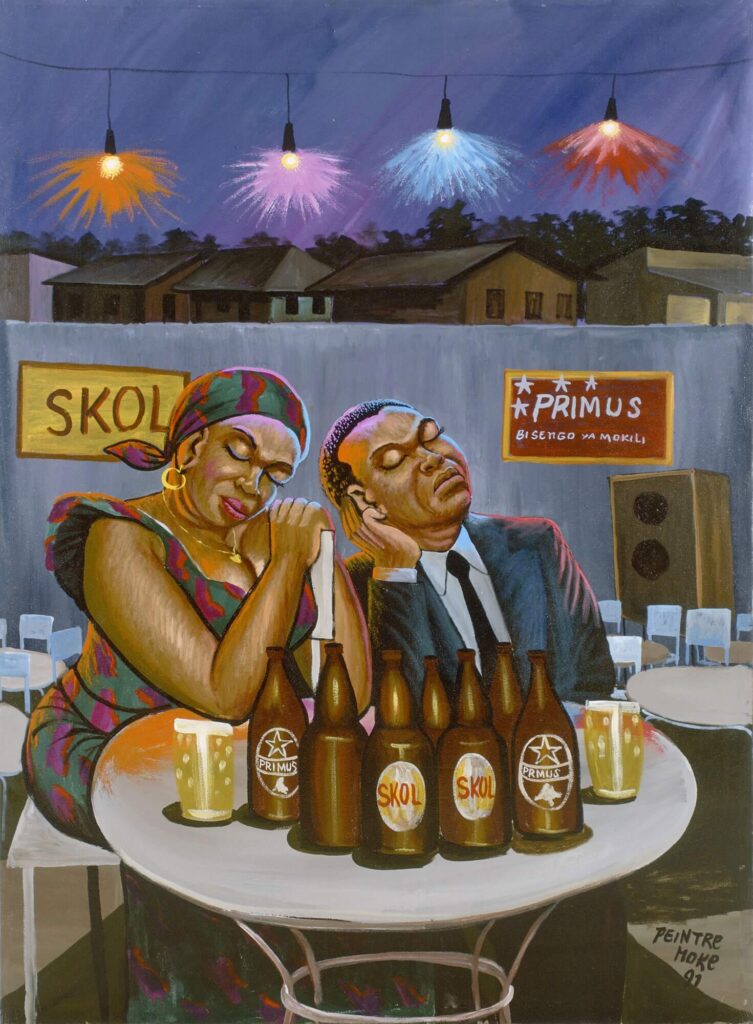

Moke

Rigobert Nimi

Bodys Isek Kingelez

Explore Further

This article is just one part of a larger conversation. To continue exploring the complex relationship between art, power, and perception, we invite you to read these related pieces on our site.

- On the Pervasive Issue of Exoticization: To understand how the Western gaze has historically shaped the depiction of African women in art, read our article: Breaking the Cycle: Confronting the Exoticization of African Women in Art.

- On Art’s Role During Belgian Colonization: For a critical look at how art was used as a tool of propaganda and control, we recommend: The Illusion of Art: Le Hangar and the Colonial Propaganda and The Untold Story of Antoinette Lubaki.

- For More of the Beauty: To see more of the extraordinary contemporary works discussed in this piece, we encourage you to explore the Congolese artists featured in the Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection.

Comments