A year ago I stood before the thunder of Zongo Falls. I took my photographs, felt the spray on my skin, and left thinking I understood what I had seen: a spectacle of raw, untamed nature. Still, a faint resonance trailed me home, the sense that I had heard only the surface of a larger song.

Weeks later in Kinshasa, a friend smiled and asked, “Did you find the Zongo garden? The creation tree?” My blank look answered for me. That afternoon opened a door to the Kongo cosmos.

What follows is a tale of two visits: one physical, one intellectual. The first was mine alone, a tourist’s encounter with a waterfall. The second belongs to centuries of misreading, and to the voice that finally set the record straight. This is the story of how the Bakongo see their world, why outsiders got it wrong, and what changes when we finally listen to those who live inside the story.

What began as a touristic attraction became an education in seeing. Not just looking at a place, but understanding the stories it carries. This is what I learned about the Bakongo worldview, and why hearing it from those who live it matters.

Reading the Wrong Map

“The European is in a hurry to learn, therefore cannot understand in depth.” —Bakongo proverb, quoted in Fu-Kiau (1969, p. 107)

I began with Joseph Van Wing’s, Bakongo Studies, Vol. II: Religion and Magic. The book is careful and exhaustive, yet something in it rang hollow. Only when I found the work of Fu-Kiau kia Bunseki-Lumanisa, a Congolese historian and initiated practitioner, did the shapes align. The world I had been reading about was not wrong in Van Wing, only bent by the perspective of his time and faith.

As the Bakongo say: “L’Européen est pressé d’apprendre, par conséquent il ne peut comprendre en profondeur.” The European is in a hurry to learn, therefore cannot understand in depth.

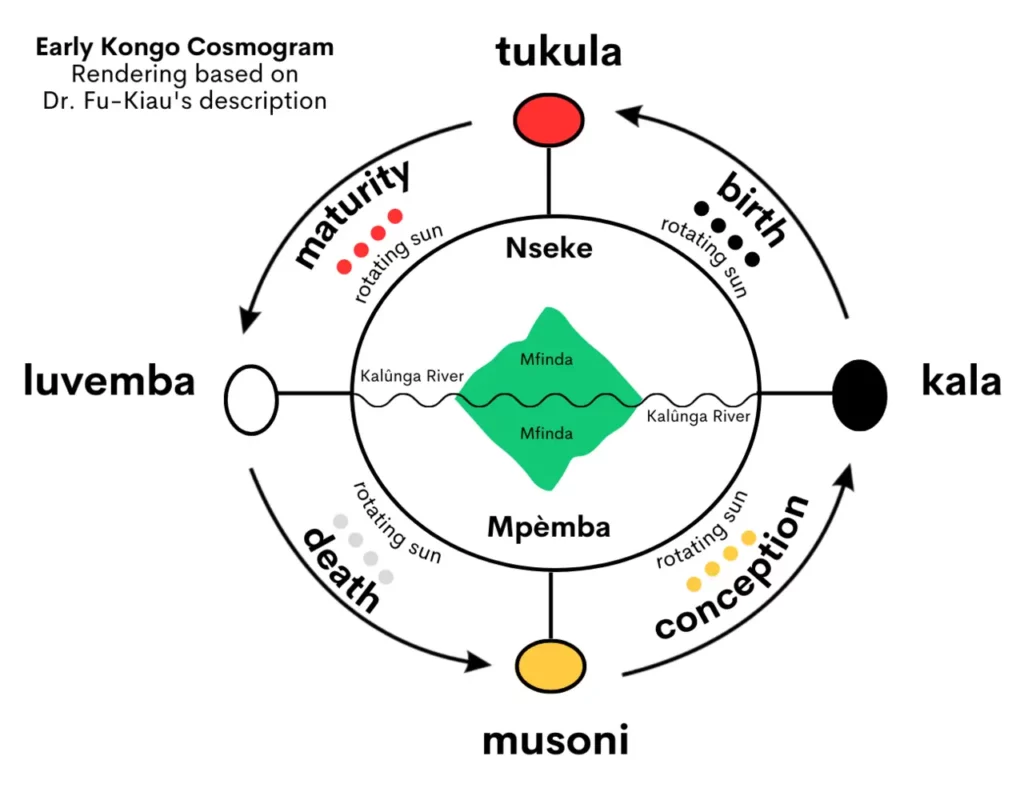

Consider a single figure: the cross. When Europeans saw crosses in Kongo, they celebrated what they thought was proof of ancient Christian influence. But the Bakongo had long drawn their own cross, a map of something entirely different: the path of the sun from dawn through noon to dusk and midnight, the soul’s journey through birth, maturity, death, and rebirth, the four moments of existence. The intersection was not Calvary but the moment when the worlds of living and dead meet.

It is a difference that begins small and ends everywhere.

These misreadings weren’t innocent mistakes. They justified interventions, dismantled schools of initiation as “secret societies,” recast philosophy as “superstition,” and sacred objects as “fetish.” Nearly erasing sophisticated systems of thought. The primitives had to be civilized!

What follows is the story that took shape once I began to listen from inside the tradition rather than from the edge.

The Architecture of Creation

“You are the meat of God. Do not be surprised when He calls you to the table.” —Fu-Kiau kia Bunseki-Lumanisa

To understand how the Bakongo see creation, forget Genesis. Instead, imagine cooking.

Creation in this cosmos is not the tale of a fall but the unveiling of a design. Nzambi a Mpungu, the Creator, makes a single, complete being named Mahungu, containing both male and female principles. To set the world in motion, Nzambi introduces a catalyst: a great forbidden tree. He then gives Mahungu the one ingredient that guarantees change: curiosity. The rule not to circle the tree is not a moral trap. It is a key. When Mahungu finally circles it, the being divides into man and woman. Perfection yields to movement. Wholeness opens the door to growth.

Fu-Kiau frames the design in one line that rearranges the room: “Nzambi prepared fufu and took humans as meat.”

Picture a vast ball of fufu standing for the world. A meal needs substance, so humanity becomes the meat. One perfect being would be a single grain on an enormous plate; a people is required. While Nzambi waits for humanity to multiply, the fufu cools and changes. Cracks rise into mountains. Seeping water becomes rivers and oceans. Spoilage feeds plants. The hardened crust becomes the ground beneath our feet. When Mahungu divides, the timer starts. The kitchen is ready. Life can multiply.

This is not primitive metaphor but sophisticated philosophy: the world as process, not product; creation as transformation, not magic; humanity as necessary ingredient, not afterthought.

Nzambi did not micromanage His creation; He built the conditions for it to unfold and became its eternal spectator. The forbidden tree was not a test of morality; it was a biological trigger. Our seeming incompleteness is not a punishment; it is the very engine of existence.

The Divine Family Drama

“Make your plans by the sun’s path; the moon cannot be trusted.” —Bakongo proverb, quoted in Fu-Kiau (1969, p. 127)

Nzambi a Mpungu is not a solitary maker but the head of a family whose relations power the sky. His wife, often named Nzambici, is Earth itself, the vessel that holds and sustains. He is spark; she is substance. Their children? They animate the heavens.

The Sun is steady and strong, rising and setting with a rhythm that rarely surprises. He is pure masculine principle, reliable as the kikongo proverb advises: “Make your plans by the Sun’s path; the moon cannot be trusted.”

But the Moon carries within herself an echo of Mahungu’s original wholeness. She is nkwa-luzungu, one who possesses both natures. By day she appears as wife to her brother Sun. By night she emerges as husband to the Stars. This double nature makes her the cosmos’s great trickster. She promises and lies, appears and vanishes, waxes full with promise and shrinks to nothing.

Because of the Moon’s double role, neither Sun nor Stars can rest. The Sun thinks the Stars are his wife’s secret lovers. The Stars believe the Sun is their husband’s other woman. Both chase the Moon seeking exclusive claim to what cannot be exclusively claimed. The Moon, meanwhile, continues her dance between forms, sometimes seen with the Sun in daylight, sometimes reigning over the Star-filled night, never fully possessed by either.

This tension is the engine of a living sky. The eternal pursuit keeps the heavens in motion, ensures the tides pull and release, makes women’s bodies follow lunar rhythms. What looks like celestial dysfunction is actually cosmic design. The Moon’s refusal to be one thing keeps everything moving.

The Bakongo read this drama nightly. When the Moon appears during day, they see her visiting her husband. When she rules the night among Stars, she tends her other marriage. Her changing face is not weakness but the very power that makes her indispensable: like Mahungu before the split, she contains all possibilities. Unlike Mahungu, she refuses to choose.

The Two-Story Universe

“Death is by no means the end of a man’s life; it is merely a turn in the road.” —Fu-Kiau kia Bunseki-Lumanisa

The Kongo cosmos is not heaven above and earth below. It is, as Fu-Kiau describes, two mountains that face each other at their bases, separated by water. The living occupy the upper mountain. The ancestors inhabit the lower mountain, Mpemba. Between them runs an ocean called kalunga. It is not a barrier but a border between two active republics.

This is not a hierarchy. It is a shift system.

When the sun sets here, it rises in Mpemba. While we work, the dead sleep. While we sleep, they work under the same sun taking its turn below. Death is not ascension to heaven or descent to hell. It is transfer to the night shift.

The cross that Europeans celebrated as Christian proof was already ancient in Kongo, mapping this very system. The horizontal line is the water between worlds. The vertical connects noon to midnight. The four points track the soul like the sun: rising at dawn as a child, blazing at noon in full maturity, setting as an elder passing on wisdom, existing at midnight in the ancestors’ realm before rising again. This is not Calvary. It is a diagram of how everything works. The map of existence.

When an elder pours wine on the ground, she is not worshipping or offering sacrifice. She greets the neighbors downstairs, maintains the treaty between floors. The recently dead can be called by name because they haven’t vanished; they’ve relocated. They visit dreams not as spirits breaking through from another dimension, but as neighbors dropping by from the lower floor.

In this cosmos, your grandmother is not in heaven or haunting the earth. She is downstairs, working her shift, available for consultation. Prayer is not vertical supplication but horizontal conversation. Death is not mystery but logistics; a change of address in a universe that runs all day and all night, where everyone keeps working, just on different schedules.

The Organ That Connects It All

“The name does not die.” —Bakongo saying, quoted in Fu-Kiau (1969, p. [45])

Now we can understand how a person fits into this vast machine. The mechanism is the name.

In Kongo thought, a name is not a label but a spiritual organ. It works as a dual connector. Internally, it seals body, life-force, and awareness into a complete person. But externally; and this is the revelation; the name is what plugs you into the cosmos itself.

When a child receives a name, they receive their star. The name assigns them coordinates in the universe, a position on the wheel, a place in the shift system between worlds. Without a name, you exist outside the system. Unsealed, uninstalled, unable to properly move between floors when your time comes.

This is why the Bakongo say: “The name does not die.”

The name is the only component that works in both worlds. When you move from sunset to midnight, from the upper mountain to the lower, your body becomes a corpse and your life-force relocates, but the name remains operative. It is the permanent address through which the living can reach you after hours and through which you can respond. To call someone’s name is not metaphor; it is dialing across the water boundary.

Names carry genealogy, creating a spiral of connection that winds back through time. Your name plus your father’s name, plus his father’s name, and on and on. Each rotation takes you deeper into the past, through all the sunrise-to-midnight journeys, spiraling back toward Mahungu, the original wholeness before the split. Each name in this spiral is both an individual star and part of a constellation that spans both mountains and all of time.

Before division, Mahungu needed no star because he was complete, containing all possibilities in one name. After the split, the separated beings needed names not just to identify them but to install them into this new cosmos where time spirals forward, generation after generation, each name adding another turn to the spiral while maintaining the thread back to the beginning.

To name is to add another coil to the spiral. To forget a name threatens to break the thread. To speak a name confirms that death is just a transfer in a universe where everyone; above and below, past and present; remains connected through the spiral of names that never dies.

Reclaiming the Narrative

For centuries, the story of the Kongo, like that of so many cultures, was told almost exclusively by outsiders. Missionaries and ethnographers arrived with their own maps of reality and, unable to read the local one, declared it a primitive sketch. This was not simple mistranslation; it was erasure.

This is why Fu-Kiau kia Bunseki-Lumanisa’s work is not just important; it is restoration. He wrote not as a historian, but as a nganga; an initiated master of Kongo tradition. He wasn’t guessing at meanings; he was explaining the operating system from inside. Without his voice, we would be left with Van Wing’s meticulous but distorted account. Ingredients without the divine recipe. We would see the cross as Christian artifact, libations as “ancestor worship,” the entire cosmic architecture as quaint folktales. Fu-Kiau provided the key: a culture’s philosophy is best understood in its own language.

Returning to Zongo Falls becomes more than personal journey. It re-enacts this very process. The first visit was the colonial encounter. I saw nature’s spectacle, took photos, left with superficial understanding. The return was different. Guided by insider insight, I began to decolonize my mind. Pouring a libation was no longer an empty gesture. It became a deliberate choice to honor the local map, to engage with sophisticated protocol, to acknowledge a worldview almost silenced.

Once you learn to read the Kongo cosmos, the sky never looks quite the same. But don’t misunderstand me; each place holds its own cosmos. The moon above the Congo dances between two marriages, while the moon above my new home surely keeps different secrets. Every sky has its story, inseparable from the land below; from its people.

To truly understand a place is not to impose foreign meanings upon it, but to learn the story it has been telling all along. To hear that story in its own language, from its own masters. this is not just an act of learning. It is an act of justice.

Sources and Further Reading

- Primary Source: Fu-Kiau kia Bunseki-Lumanisa. Le Mukongo et le Monde qui l’Entourait: Cosmogonie-Kongo [The Mukongo and the World that Surrounded Him: Kongo Cosmogony]. Kinshasa: Office National de la Recherche et de Développement, 1969. Translated from Kikongo by C. Zamenga-Batukezanga. The essential text—written by an initiated nganga of the Lemba society, providing an insider’s view of Kongo cosmology and philosophy.

- For Comparison: Van Wing, Joseph. Etudes Bakongo: Sociologie, Religion et Magie [Bakongo Studies: Sociology, Religion and Magic]. 2nd edition. Bruges: Desclée de Brouwer, 1959. A meticulous external observation by a Belgian missionary—valuable for its detail but limited by its outsider perspective.

Comments