The Democratic Republic of Congo is a land where art thrives in the shadows of struggle and the glow of resilience. While global attention often fixates on Congolese music—a vibrant force in its own right—the nation’s visual artists have quietly forged a parallel revolution. Their canvases pulse with untold stories, ancestral whispers, and audacious visions of the future. Yet for every Chéri Samba celebrated in Parisian galleries, there are countless others painting in Kinshasa’s backstreets, their brilliance overlooked by a world that still views Congolese art through a colonial lens.

This list of 11 painters is not a ranking, but an invitation to explore Conogolese art. Many fought for recognition against staggering odds, while others remain unsung heroes, their work bartered for rent money or tucked into the corners of makeshift studios. Fame here is a fickle dance: European collectors and curators often dictate who “matters,” leaving talent to simmer in obscurity.

The divide is stark. On one side stands the Académie des Beaux-Arts, a colonial-era institution where European techniques are taught to those who can afford its fees. On the other, the École Populaire—a grassroots network of mentorship. Masters like Chéri Chérin and Moke open their studios to street kids and teenage apprentices, trading formal lessons for practical skills: how to make canvases from repurposed materials, create pigments from natural sources, or paint billboards by day to fund personal art by night.

What unites them? A refusal to surrender. These artists are construction workers, sign painters, and entrepreunerus by necessity, poets and prophets by choice. Their work is not just about beauty—it is survival. As we explore these 11 names, remember: each one represents a hundred others still waiting in the wings. Their stories are Congo’s heartbeat, urgent and unamplified. Let’s listen.

Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu (1947-1981): Congo’s Visual Historian

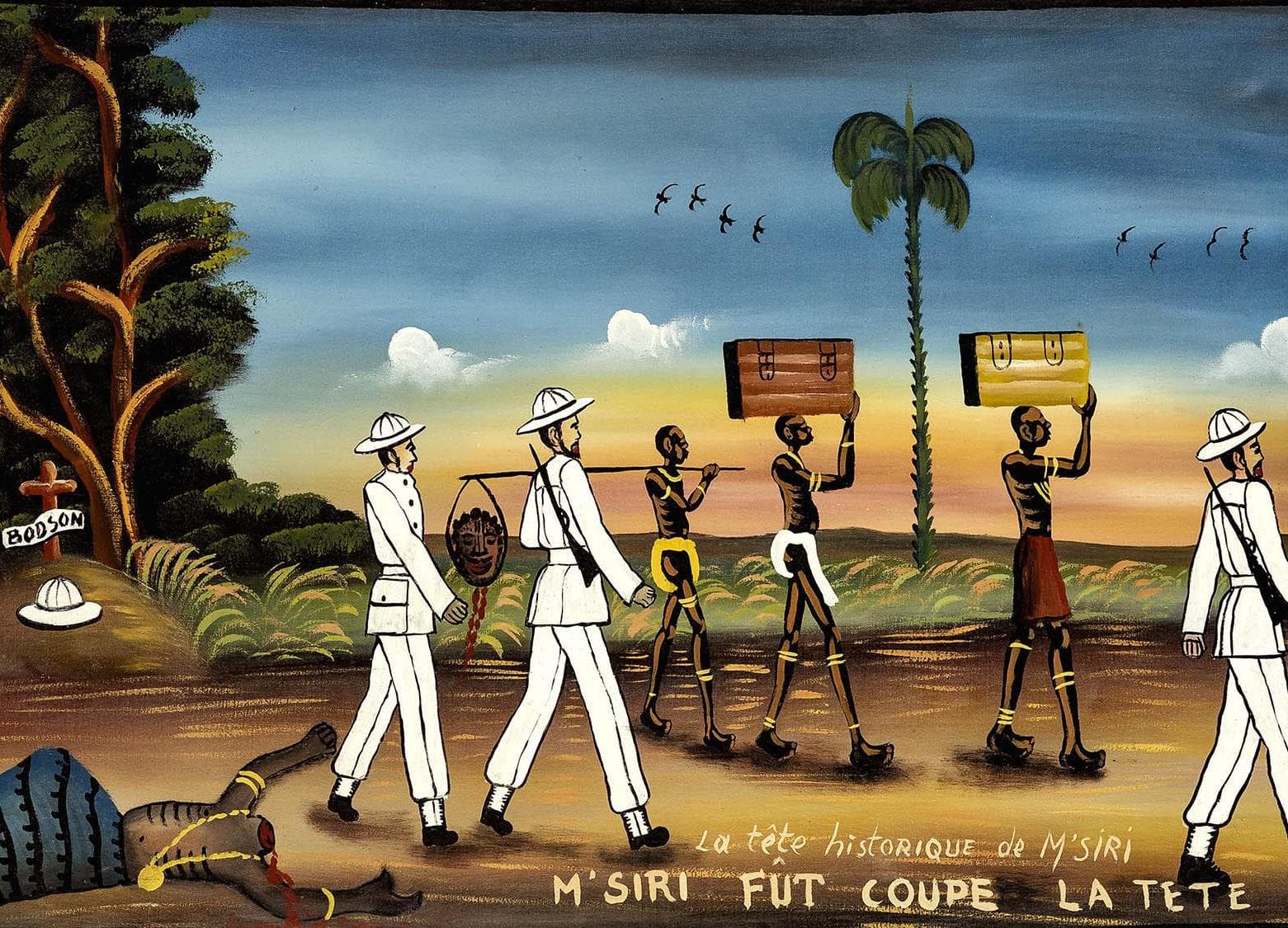

A self-taught visionary of the École Populaire, Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu traded colonial textbooks for brushes, chronicling Congo’s past in 100 explosive paintings. His “L’Histoire du Zaïre” series—from Stanley’s violence to Mobutu’s theatrics—tells history through the people’s eyes: bold, symbolic, and defiant. In “The Head of M’siri”, he resurrects a decapitated anti-colonial king, turning folklore into potent resistance. His bold, deceptively simple style conveys profound historical narratives with striking clarity.

“History is not in books, but in the people.” —Tshibumba Kanda-Matulu

Collaborating with German sociologist Johannes Fabian in “Remembering the Present”, he integrated art with oral histories, proclaiming, “Our truth lives in the streets, not museums.” Yet his genius was often undervalued and exploited. He painted on scraps, sold works for minimal profit to European academics, his art commodified even as it critiqued the very systems that marginalized him.

Tragically, Tshibumba vanished mysteriously in 1981—a ghosted critic of Mobutu’s regime. His disappearance remains a chilling reminder of the dangers faced by those who dared to challenge the status quo. Today, his work stands as a powerful testament to the importance of reclaiming and preserving history from the people’s perspective.

Chéri Samba (b. 1956): Master of Colors

If Tshibumba painted history’s wounds, Chéri Samba reflects its present, wielding satire like a neon-lit paintbrush. Rising from a sign painter’s apprenticeship in Kinshasa’s bustling markets, Samba pioneered “problem paintings”—blending text, portraiture, and social commentary into electric dialogues. His signature style transforms everyday scenes into theatrical stages where corruption, sexuality, and postcolonial identity collide in vivid color.

“Our lives are full of color. Our struggles are colorful too.” —Chéri Samba

Samba’s brilliance is in making the local universal. Whether tackling AIDS awareness, political hypocrisy, or the burden of tradition, his canvases communicate without words. Text bubbles thread through his compositions, transforming his paintings into global conversations while remaining deeply anchored in Congolese life. Now largely based in Europe, his work continues to echo the rhythms of Kinshasa, proving that distance can sharpen rather than weaken an artist’s connection to home.

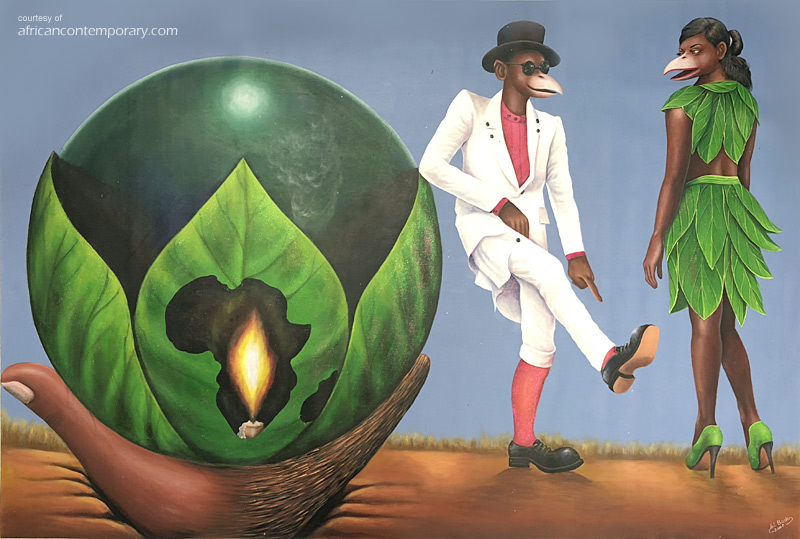

Pierre Bodo (1953-2015): The Fashionista

Pierre Bodo, rooted in Kinshasa’s vibrant “sapeur” culture, created canvases that shimmer with an otherworldly elegance. Like Samba, he began as a sign painter, but Bodo’s artistic journey explored the intersection of fashion, spirituality, and social status. His paintings capture a uniquely Congolese phenomenon: clothing as both armor and rebellion.

Bodo’s figures exude elegance—elongated silhouettes in dazzling suits, mystical beings adorned in surreal, flowing patterns. Beneath the flamboyance lies a profound reflection on postcolonial identity. His “La Sape” series elevates street fashion to a near-religious ritual, each garment a prayer for dignity.

“I express everything that happens to me, so that I am no longer focused on specifically African topics and can address myself to the entire world.” —Pierre Bodo

Perhaps his most striking works bridge the material and spiritual. Through Bodo’s brush, Kinshasa’s street culture achieves mythological status, ancient spirits reborn as contemporary fashion icons. With his passing in 2015, Congo lost not just a painter, but a visionary who understood that in hardship, style itself is resistance.

Chéri Chérin (b. 1955): The People’s Painter

Chéri Chérin, a contemporary of Samba and Bodo, paints with raw, unvarnished energy that captures the pulse of Kinshasa. His canvases are crowded, chaotic, and bursting with life, reflecting the city’s vibrant street culture. Unlike Samba’s polished commentary or Bodo’s ethereal visions, Chérin’s work feels immediate, almost journalistic. He documents everyday struggles and triumphs, portraying market women, musicians, and street vendors with heroic dignity. As Chérin himself states, art flowed through his veins from birth; he was born, he says, with a pencil in his hand.

“Peinture populaire is an artistic declaration of our independence, asserting the right to portray our realities through our own lens, free from the constraints of foreign artistic standards.” —Chéri Chérin

A pioneer of peinture populaire, Chérin deliberately eschewed formal training at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, choosing instead to cultivate his unique vision. His commitment to depicting the lived experiences of the Congolese people remains at the heart of his artistic philosophy, making his work a powerful testament to the strength and vitality of his community.

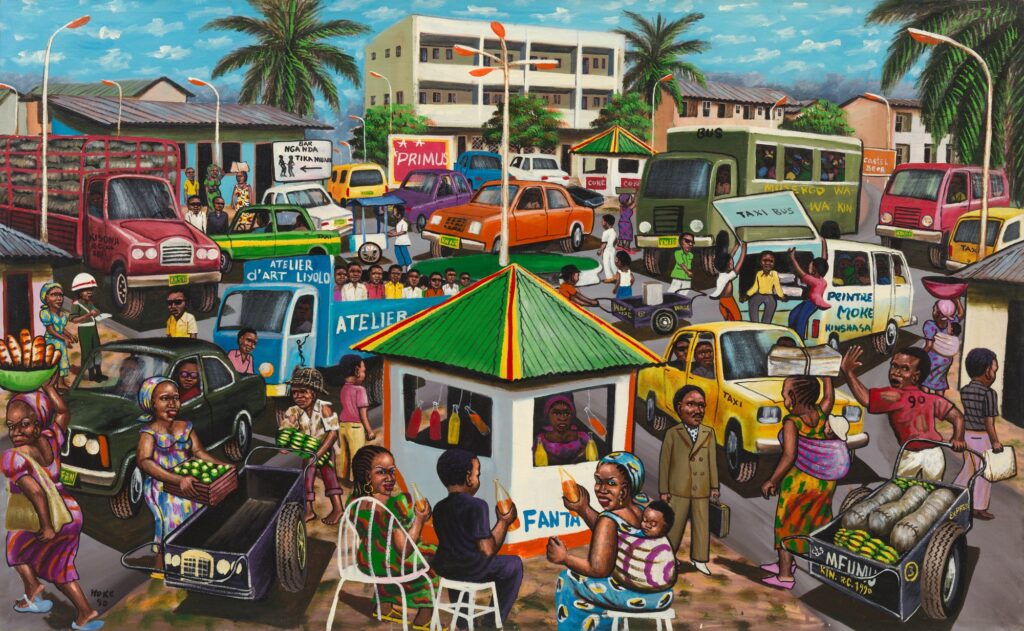

Moke (1950-2001): The Urban Chronicler

While Bodo elevated fashion to myth, Moke kept his feet firmly planted in Kinshasa’s red earth, earning his title as the “painter of urban life.” Born Monsengwo Kejwamfi, he arrived in the capital as a street child, armed with nothing but raw talent and an eye for capturing a city in mid-transformation. Where others saw chaos in Kinshasa’s crowded bars and bustling markets, Moke found poetry in motion.

“I paint what I see.” —Moke

With a brush as swift as the city’s rhythm, Moke developed a distinctive style: quick, gestural strokes that vibrate with the raw energy of urban life. His canvases pulse with lovers in shadowy bars, politicians in gleaming cars, and market women beneath kaleidoscopic umbrellas. Unlike his contemporaries who often incorporated text or symbolic elements, Moke let his scenes speak through pure visual narrative, transforming the everyday tumult of Kinshasa into electric tableaux of power, desire, and survival.

Pilipili Mulongoy (1914-2001): The Master of Movement and Nature

Before Kinshasa’s artistic revolution, Pilipili Mulongoy worked under the colonial framework of the Atelier du Hangar in Lubumbashi. Although initially restricted to natural subjects, Pilipili created something extraordinary—a visual language that captured the fluid essence of the living world with unprecedented mastery.

“Nature moves when you truly look at it. Everything is connected, always dancing.” —Pilipili Mulongoy

Despite working with a restricted palette, Pilipili transformed colonial expectations into works of staggering complexity and movement. Birds sweep through compositions in elegant arcs, fish ripple across the canvas, and vines seem to dance with life. Each piece unveils new details with every viewing, proving that artistic genius can flourish even within imposed constraints. His legacy is a testament not just to technical brilliance, but to the power of African artists to transcend the limitations placed upon them.

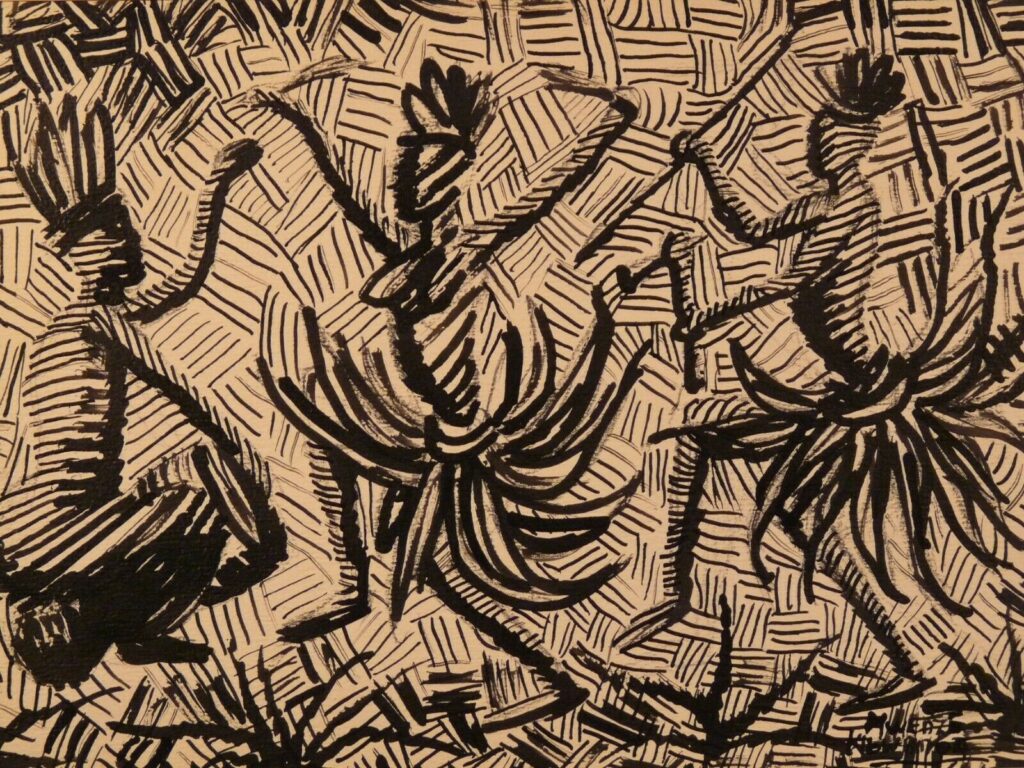

Mwenze Kibwanga (1925-1999): The Modern Traditionalist

Like his contemporary Pilipili Mulongoy, Mwenze Kibwanga emerged from the structured environment of Lubumbashi’s Atelier du Hangar. Under Pierre Romain-Desfossés’s colonial patronage, he was directed toward specific subjects and styles. Yet, Mwenze’s approach transformed these constraints into something remarkable—geometric precision that redefined African motifs in a modernist language.

“Each line must have its purpose, its rhythm, its truth.” —Mwenze Kibwanga

Working primarily in black ink on white paper, Mwenze developed a signature style of intricate parallel lines and dynamic geometric patterns. His subjects—hunters, dancers, and animals—appear caught in moments of intense concentration, their forms pulsating with rhythmic energy. Though the Atelier dictated his themes, Mwenze’s mathematical precision and innovative abstraction laid the groundwork for future generations of African modernists.

Pathy Tshindele (b. 1973): The Congolese Basquiat

Where earlier generations worked within defined forms, Pathy Tshindele shattered conventions. His canvases explode with raw energy—a chaotic fusion of graffiti, traditional symbols, and contemporary iconography that earned him comparisons to Jean-Michel Basquiat. Yet, Tshindele’s visual language is uniquely Congolese, shaped by Kinshasa’s urban grit and the spiritual resonance of ancestral masks.

“I paint chaos because we live chaos. Beauty hides in the fragments.” —Pathy Tshindele

His figures emerge from dense layers of paint and text—distorted faces screaming silent protests, bodies twisted under history’s weight, all rendered in a fever-dream palette. Tshindele’s art is both accusation and prophecy, integrating comic-book elements, ad boards, and ritual objects into a searing commentary on modern Congo. Through fearless experimentation, he bridges the gap between popular painting and contemporary art, proving that tradition and revolution can coexist on the same canvas.

Steve Bandoma (b. 1981): The Mixed Media Revolutionary

After the raw intensity of Tshindele’s work, Steve Bandoma pushes Congolese art further into experimental terrain. Trained at the Académie des Beaux-Arts but rejecting its conservative approach, Bandoma dismantles notions of what “Congolese art” should be. His mixed-media works—watercolor, collage, found objects—erupt in compositions that challenge both tradition and modernity.

Bandoma’s figures are often grotesque hybrids—bodies constructed from fashion magazine cutouts, traditional masks, and corporate logos, all drowning in washes of violent color. Political figures morph into monsters, colonial imagery is dismembered and reassembled, and consumer culture collides with spiritual iconography.

“I don’t make pretty pictures. I dissect reality, then rebuild it my way.” —Steve Bandoma

His radical approach creates a new visual language to explore Congo’s intricate identity in an era of globalization.

JP Mika (b. 1980): The Virtuoso of Joy

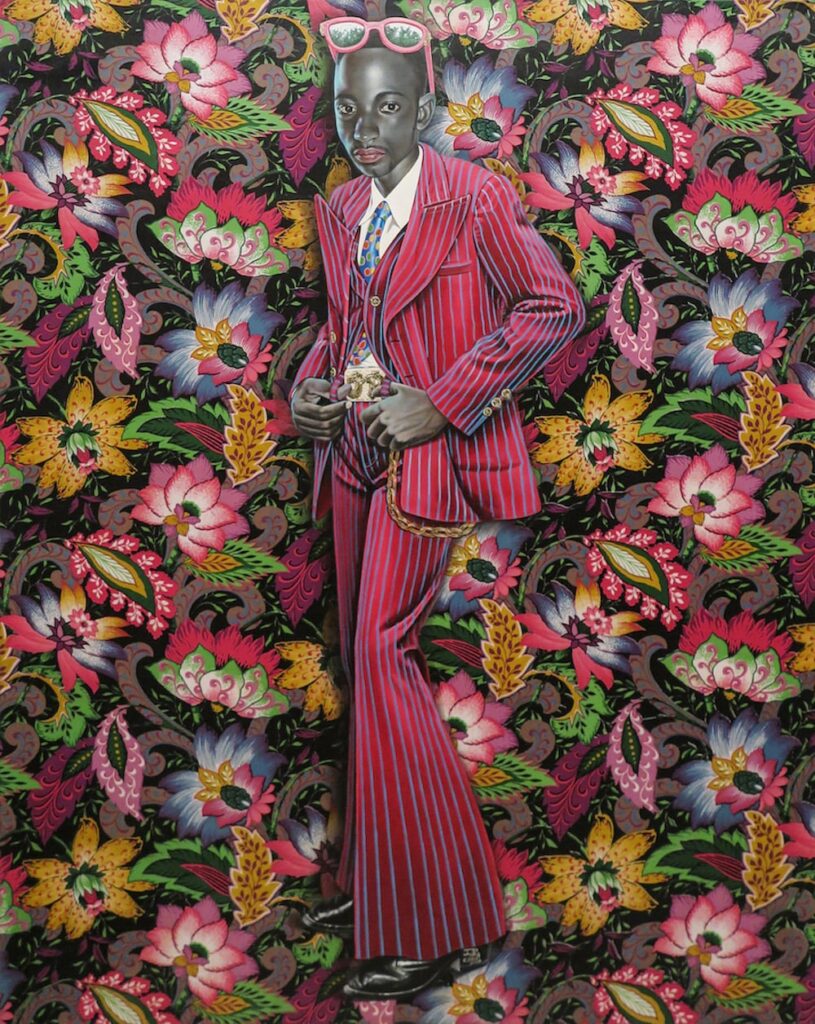

In a lineage marked by political critique and social commentary, JP Mika stands apart with his dazzling celebrations of Congolese life. A former student of Chéri Chérin who has since developed his own distinctive voice, Mika transforms portraiture into pure visual ecstasy. His canvases showcase exceptional technical precision, where every fold of fabric and glint of light is meticulously detailed.

“Beauty is not frivolous—it’s revolutionary. To paint joy in Congo is to resist.” —JP Mika

His signature style merges hyperrealist portraiture with intricate, patterned backgrounds that pulse with life, immersing the viewer in a world of color and movement. Subjects emerge from cascading walls of wax print fabrics, their skin glowing with an inner light that makes them appear both earthly and divine. While his predecessors used art to confront Congo’s struggles, Mika’s work suggests another form of resistance—the insistence on celebrating beauty, dignity, and joy despite everything. Through his meticulous technique and vibrant vision, he demonstrates that even in a landscape of socially charged art, there remains space for beauty and joy.

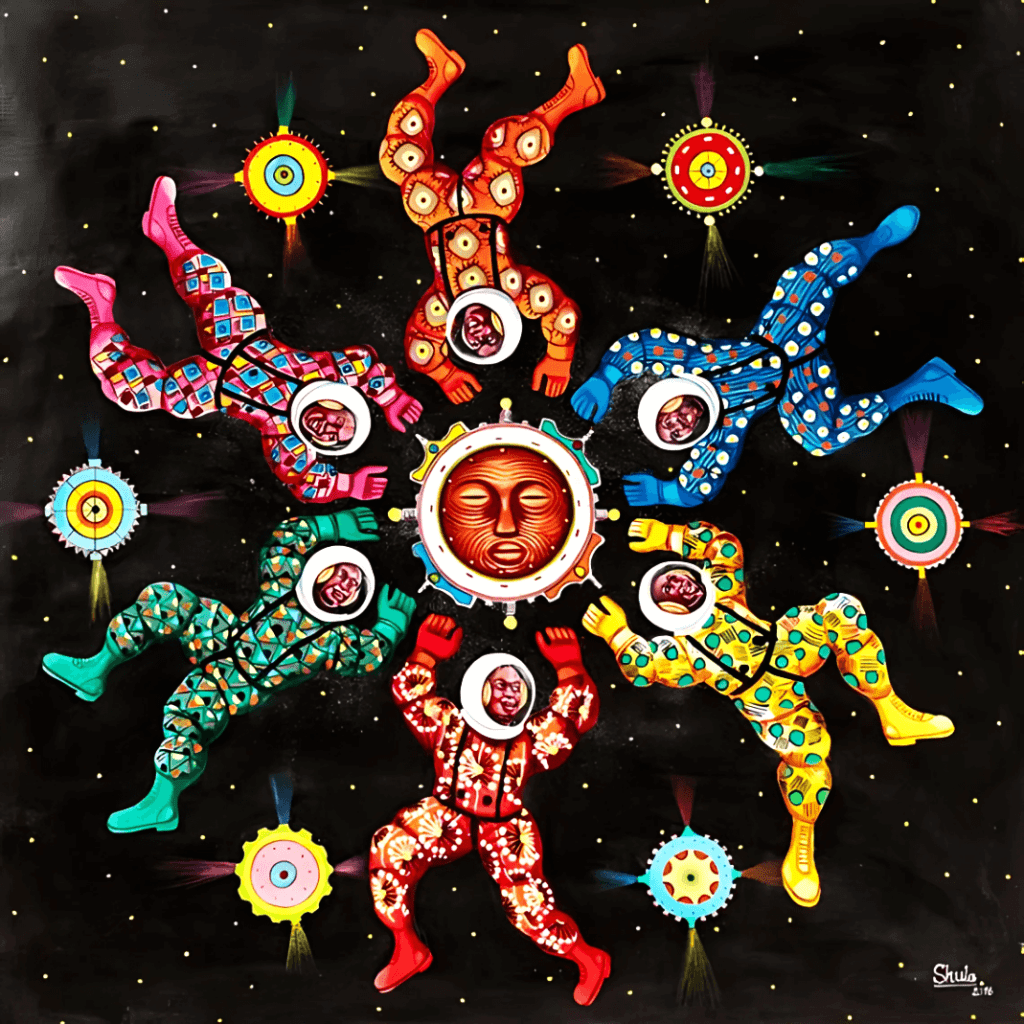

Monsengo Shula (b. 1959): The Cosmic Dreamer

Setting himself apart from peers who emphasize urban life and political commentary, Monsengo Shula explores a dreamlike realm, intertwining mysticism with science fiction. Starting as a sign painter in Kinshasa’s bustling streets, he evolved into one of Congo’s most distinctive visionaries, creating dense, dreamlike compositions where science fiction meets traditional cosmology.

“I paint what exists beyond our eyes—the forces that shape our world, invisible but real.” —Monsengo Shula

In his masterwork “Mission Inédite,” astronauts drift through a mystical cosmos wearing space suits fashioned from vibrant pagne fabric, their traditional African textile patterns creating a striking contrast with the technological setting. Using a palette of deep cosmic blues and incandescent golds, Shula weaves Congolese spiritual traditions with futuristic visions, suggesting that the gap between ancestral wisdom and scientific progress might not be as wide as we think. Through his unique fusion of the mystical and the modern, he proves that Congolese art can be both deeply rooted and radically innovative.

Conclusion

These eleven artists are not just representatives of Congolese painting; they are torchbearers of a movement that continues to redefine the nation’s cultural landscape. Their works span historical reclamations, cosmic explorations, confined expressions, and radical deconstructions, collectively illustrating an artistic evolution that defies simple categorization. Each generation has faced and transcended challenges—colonial constraints, political pressures, and economic barriers—turning adversity into a driving force for creative expression.

As African contemporary art gains traction worldwide, these artists exemplify how Congolese painting has long flourished on its own terms, now stepping confidently onto the global stage. In Kinshasa’s studios and Lubumbashi’s workshops, on recycled canvas and salvaged materials, they have always painted their truth. Their work speaks not just of struggle but of transcendence, not just of resistance but of joy.

What’s next? As JP Mika reinterprets tradition and emerging artists bring fresh perspectives, Congolese art continues to evolve—honoring its heritage while embracing new artistic frontiers. At Kitokongo, we actively seek out and nurture emerging talents across districts and cities, bridging the gap between hidden creativity and global recognition. Our mission is grassroots and essential—finding, supporting, and promoting emerging artists, doing the work that institutions often overlook. We create not just visibility but sustainability, ensuring that the next generation of Congolese artists can evolve and thrive. Somewhere in Kinshasa, an artist is transforming a simple canvas into a masterpiece, waiting for the world to witness the next chapter of Congolese art. This is the real work of artistic revolution—not just celebrating established names, but building bridges between talent and opportunity.

If you listen closely, you can almost hear the brushstrokes—each one a quiet yet undeniable force shaping the next wave of Congolese artistry. Follow our journey, support our mission, for we are doing the vital work that no one else will: ensuring that Congo’s artistic future remains as vibrant as its past.

Comments

I enjoyed your article and admire what you are doing to promote art in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. My husband and I lived in Kinshasa in 1965 for two years. I am hoping to get in touch with Artist Bosulu Stanislaus who was painting in 1966.

Can you please help me?