Why does Patrice Lumumba’s story still haunt us after more than sixty years? When Malcolm X called him “the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent,” he recognized something that Lumumba’s enemies tried desperately to erase – here was a leader who wielded words like weapons. After King Baudouin praised Belgium’s “civilizing mission” at independence, Lumumba rose unscheduled to deliver a masterful counter-speech. Without breaking diplomatic protocol, he systematically demolished colonial mythology, using the colonizers’ own language and manners to expose their contradictions. His eloquence was so threatening that Cold War politicians branded him a communist – the era’s most dangerous label – to justify his elimination.

The response of colonial powers and their allies was telling – they didn’t just kill him, they tried to erase him completely. His electrifying speeches mysteriously disappeared from archives. They tortured him, humiliated him publicly, and dissolved his body in acid to deny his people even the dignity of a grave to mourn at. For decades, all his family and nation had were memories – until 2022, when Belgium finally returned Lumumba’s tooth, kept for over 60 years by his executioner. For the Congolese people, this single tooth represented not just the return of their hero’s remains, but a chance to finally give their first Prime Minister a proper burial, to close a wound that had remained open for half a century.

Through the remarkable paintings of Congolese artist Tshibumba Kanda Matulu (TKM), we’ll trace this extraordinary journey from mine worker to martyr. Each canvas captures not just what happened, but what it meant – how one man’s vision of true independence shook the foundations of colonial power so deeply that his opponents couldn’t rest until they had eliminated not just the man, but every trace of his existence. Yet as these paintings show, some dreams refuse to die, no matter how hard you try to bury them.

Breaking Colonial Barriers: The Making of a Pan-African Voice

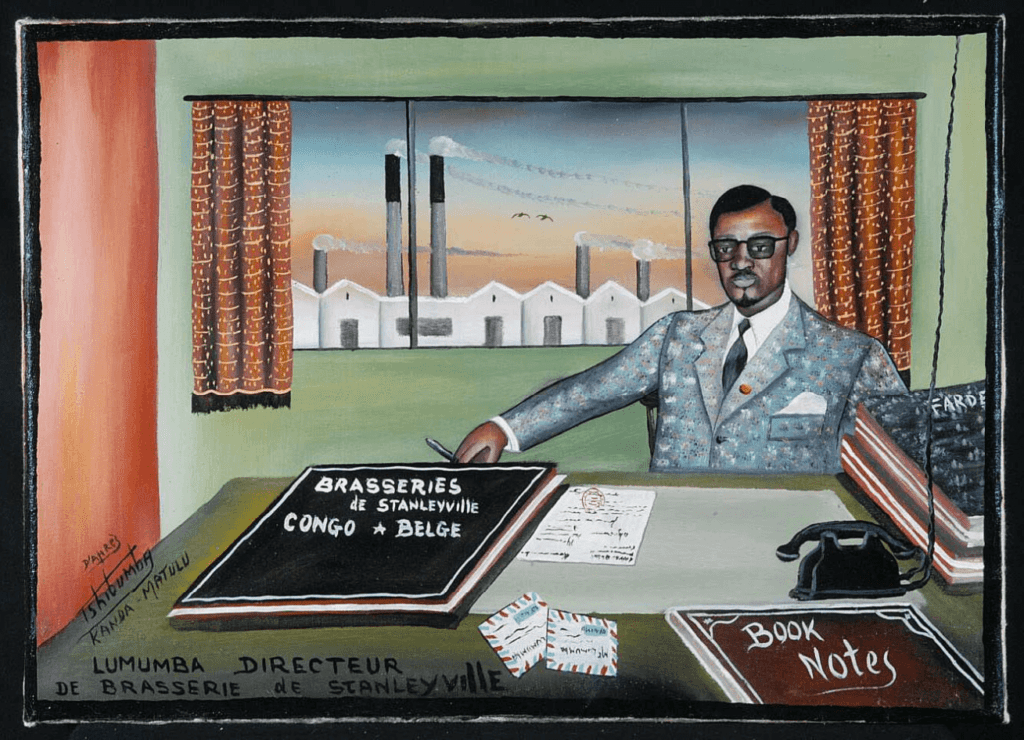

Colonial Congo was a place of rigid hierarchies, where Africans were meant to stay in their assigned place. But Patrice Lumumba refused to accept these limitations. Starting as a laborer in the mines of Kalima, he worked his way up to become a postal clerk in Stanleyville, spending his evenings in relentless self-education. The brewery recognized something special in this articulate, charismatic young man – someone who could connect with African customers better than any European. When they promoted him to Commercial Director, the first Congolese to hold such a position, it came with a European-level salary and status.

Yet even in his elegant office, with its view of industrial chimneys and desk covered in international correspondence, Lumumba was already thinking beyond personal success. As Aimé Césaire wonderfully captured in his play “A Season in the Congo,” he would turn business speeches into political messages, cleverly telling worried authorities that such talk only made people drink more beer. The brewery might have hired him to sell products, but Lumumba was quietly selling something else – the dream of freedom.

Prelude to Division: Two Leaders Cross Paths in Brussels

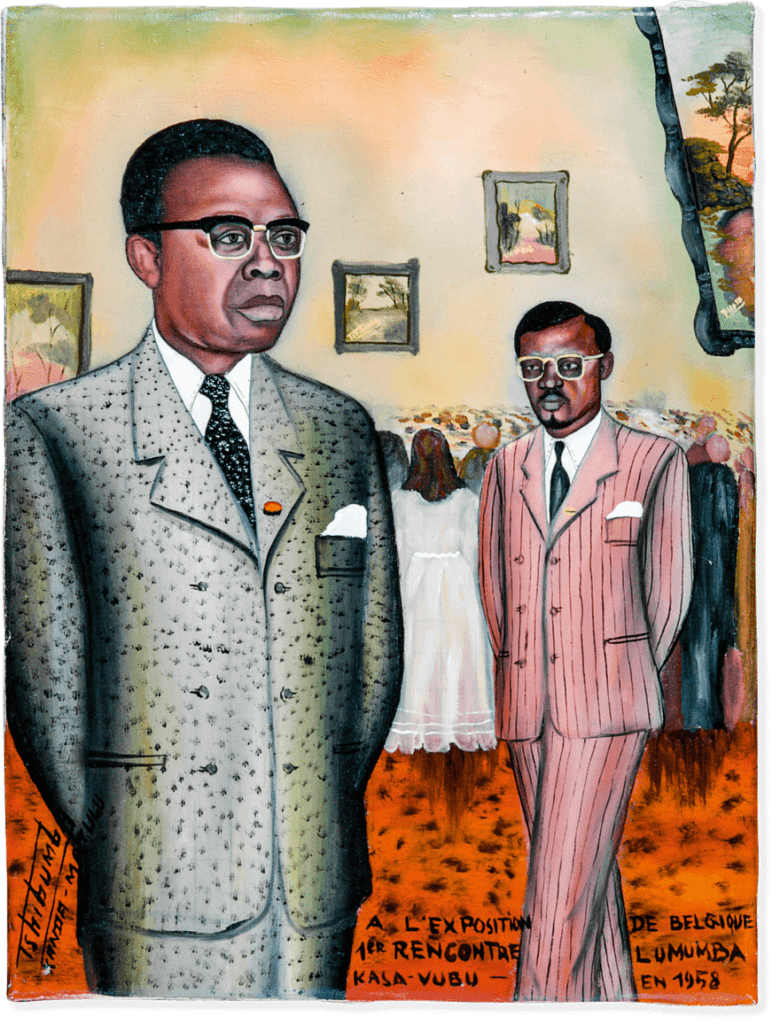

History often turns on unexpected moments. In 1958, as African nations were gaining their independence one by one, two Congolese men crossed paths at the Brussels World’s Fair in what would prove to be a decisive encounter.

Standing face to face in Belgium’s prestigious exposition are two men who shared similar backgrounds but carried vastly different dreams. Joseph Kasa-Vubu, already mayor of Dendale district in Léopoldville, stands in his conservative suit with its loyal flag pin – a man who had learned to work within the colonial system. Before him stands Lumumba, fresh from witnessing the rising tide of African liberation at the Pan-African Conference, his pink striped suit and passionate words representing a radical vision for Congo’s future.

In this chance encounter, two paths toward independence faced each other, neither man yet realizing they would soon become bitter rivals in a struggle for Congo’s soul.

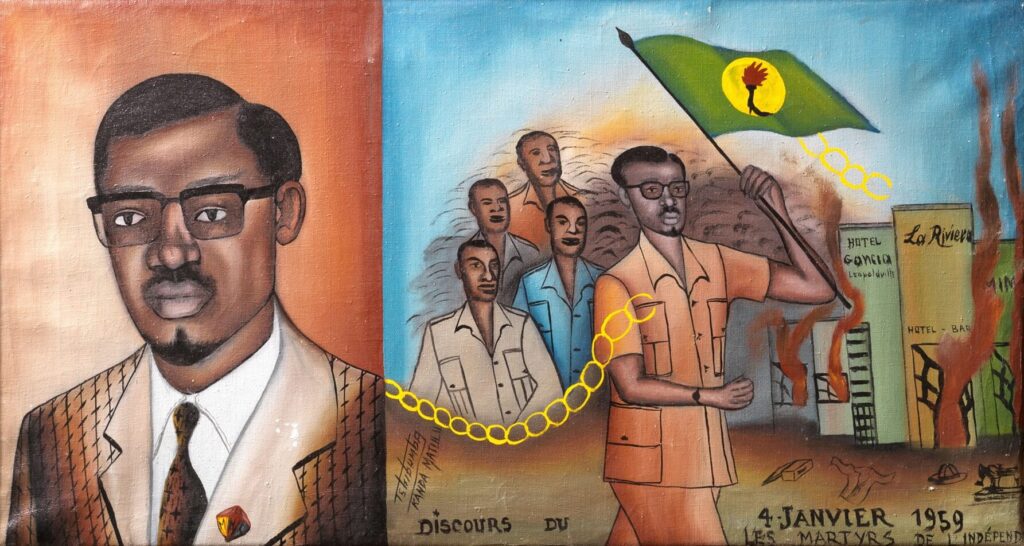

Days of Fire: 4th January 1959

A banned political rally in Léopoldville became a turning point in Congo’s independence struggle. When Kasa-Vubu addressed the crowd, calling for gradual steps toward freedom, his measured words fell flat. But when Lumumba spoke, his radical vision of immediate and complete independence ignited the crowd’s imagination. While Kasa-Vubu left early, unable to control the situation, Lumumba’s message spread like fire through the streets.

TKM captures this pivotal moment in his painting. On one side, Lumumba speaks to the crowd, his words sparking revolution. On the other, a city burns. Leopold’s statue stands empty, colonial buildings are in flames, and symbolic chains break free – just as Congo’s demands for freedom had broken free of compromise and caution. After this day, there would be no going back to polite requests for independence.

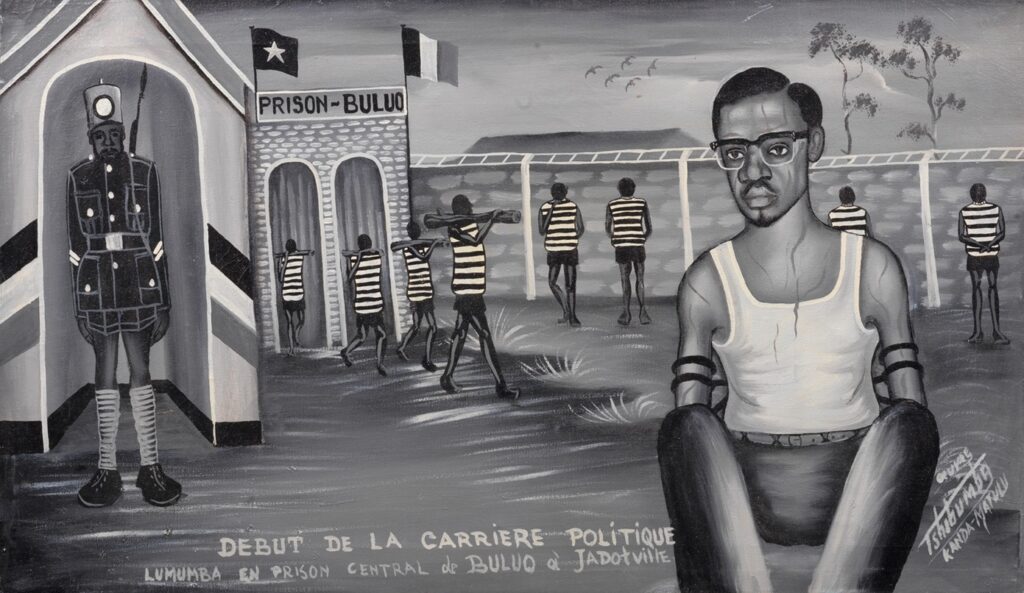

Behind Prison Walls: Where a Political Career Was Born

For their roles in the January uprising, both leaders were imprisoned. While Kasa-Vubu was arrested for demanding limited independence for Kinshasa, Lumumba was sent to Buluo prison for advocating complete national liberation. What the colonial authorities intended as punishment would ironically launch Lumumba’s true political career.

In TKM’s painting, we see the transformation begin. Gone are the business suits and corporate privileges, replaced by prison stripes and watchful guards. Yet even here, Lumumba turned his cell into a place of preparation, spending his time reading and deepening his understanding of freedom’s true meaning. The brewery director was becoming something more – a national political figure whose imprisonment would resonate with people across Congo.

When he emerged from Buluo, he was no longer just a successful businessman who spoke of politics – he was a leader who had sacrificed his freedom for his beliefs. Prison had given him what his corporate success could not: credibility as a fighter for independence.

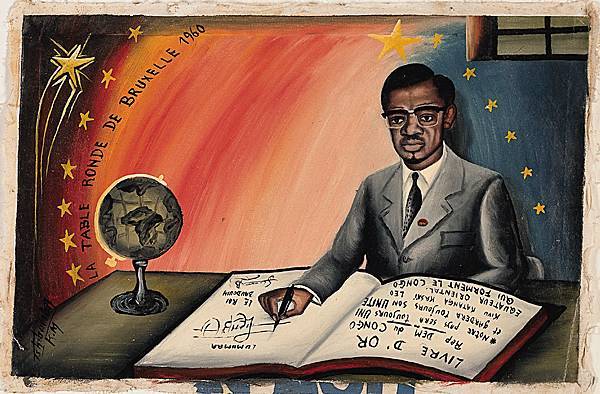

From Prison to the Negotiating Table

The Brussels Round Table Conference of 1960 marked another turning point in Lumumba’s journey. In TKM’s painting, we find him seated alone at a table, pen in hand, before a document already bearing King Baudouin’s signature – a clear sign of who truly orchestrates these proceedings. Behind him, a painted wall shows a dramatic scene – stars scatter across a red-tinged sky, while a globe tilted to show Africa stands as silent witness. The barred window at the corner completes the scene’s confined atmosphere.

Colonial authorities had hoped prison would diminish Lumumba’s influence, but his time in Buluo had only strengthened his position. Now at the negotiating table, he appears transformed – gone are his characteristic colorful, patterned suits, replaced by a plain grey one that speaks to the gravity of these proceedings. TKM captures this tension perfectly: though Lumumba sits at the table where Congo’s future will be decided, his subdued attire and expression suggest a man who understands the compromises inherent in this carefully staged moment of transition.

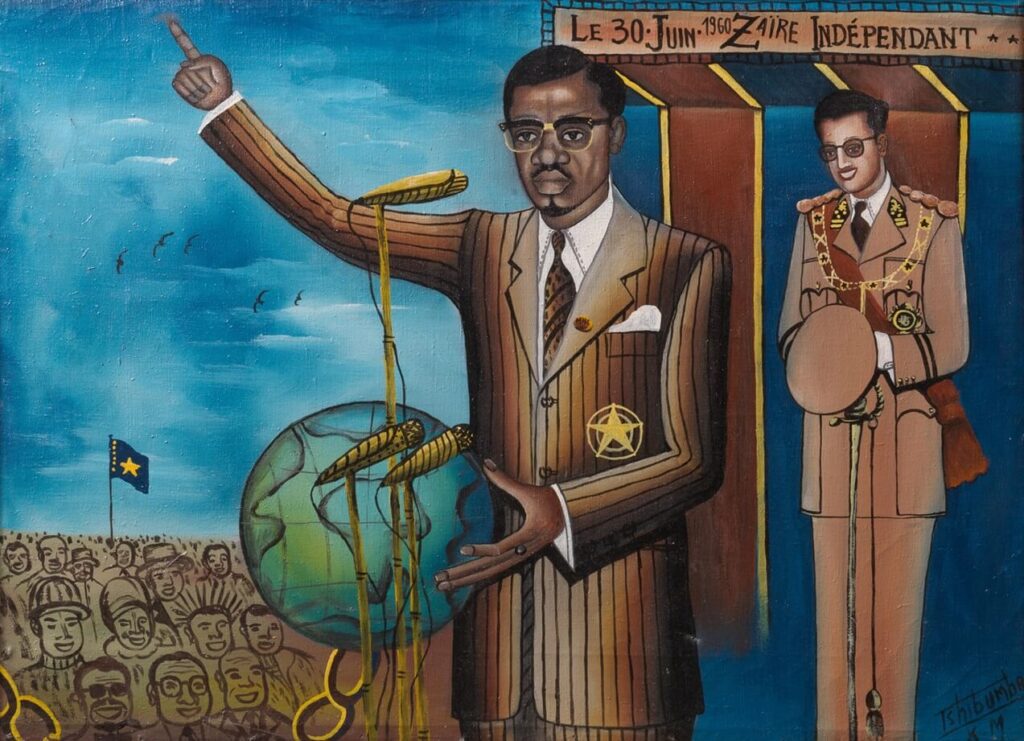

The Independence Day Speech: Truth to Power

June 30, 1960, marked a day that was meant to follow a carefully scripted ceremony. In TKM’s powerful painting, we see the moment everything changed. Lumumba stands tall in a pinstriped suit, one arm raised in oratory, while the other cradles a globe wrapped in broken chains. Behind him, King Baudouin watches with a forced smile, his ceremonial uniform and medals unable to mask his discomfort. A sea of faces fills the background, beneath the new flag of independent Congo.

The King had just finished praising Belgium’s “civilizing mission” when Lumumba rose to deliver his unscheduled response. Here was the fire that prison couldn’t extinguish, the voice that diplomatic protocols couldn’t contain. TKM captures it perfectly – while the King maintains his ceremonial pose and uncomfortable smile, Lumumba’s gestures convey the passion of a man speaking hard truths. The globe in his hands, breaking free from its chains, mirrors his words as they systematically dismantled colonial mythology.

The colonial powers would later make this speech disappear from official archives, leaving only fragments on damaged tape – as if words so powerful had to be erased to maintain the old order. Yet TKM’s painting preserves what they tried to destroy: the moment when one man’s voice shattered decades of colonial pretense, speaking not for the diplomats in the room, but for the masses of people behind him whose suffering could no longer be ignored.

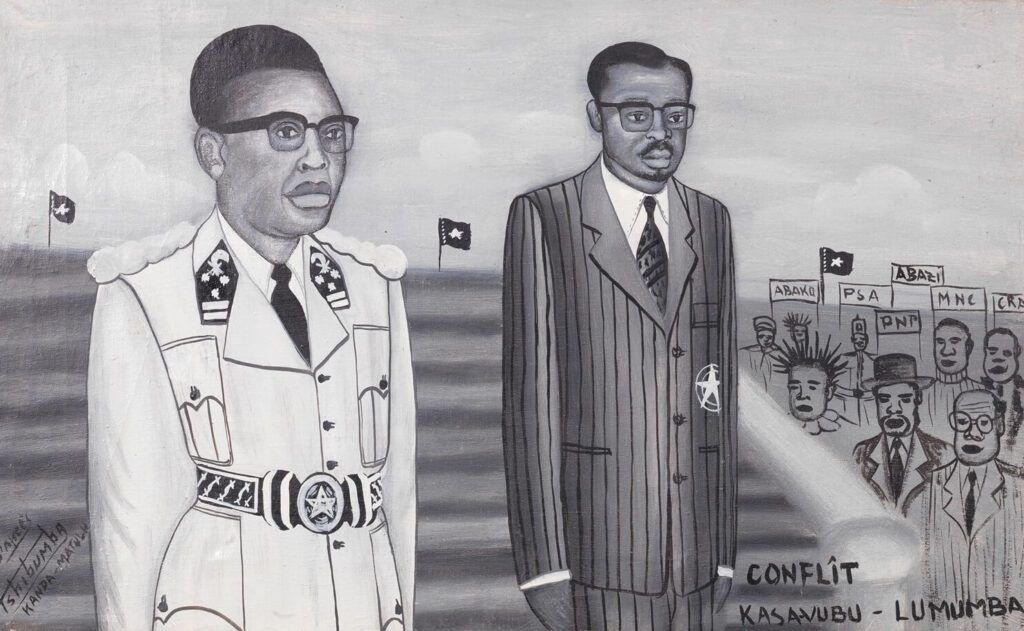

The Breaking Point: Kasa-Vubu vs. Lumumba

TKM’s second black and white painting marks another crucial turn in Lumumba’s story. Just days after independence, tensions erupted as Lumumba took an increasingly radical stance, demanding the immediate departure of all Belgians from Congo. In the painting, he stands in his dark pinstriped suit beside President Kasa-Vubu, who wears a white uniform heavy with medals and stars. The stark absence of color emphasizes the growing divide between these two leaders, while TKM’s label “CONFLIT KASAVUBU-LUMUMBA” tells us exactly what moment we’re witnessing.

Behind them, political party banners hint at the fracturing of national unity. When Kasa-Vubu publicly announced Lumumba’s dismissal as Prime Minister, Lumumba immediately rushed to the radio station to denounce him. Like the first black and white painting of his imprisonment, TKM’s monochrome palette here foreshadows darker days ahead. Without his position and the immunity it provided, Lumumba was now vulnerable to the forces that had long waited to silence him.

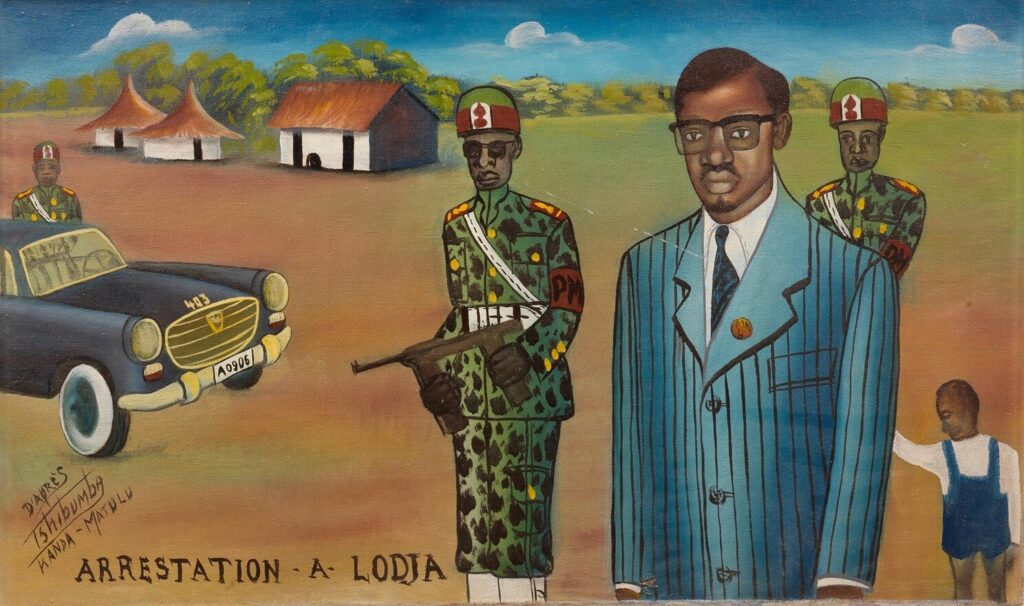

The Final Journey: Arrest at Lodja

In TKM’s vivid painting of Lumumba’s arrest, we see a scene that appears deceptively calm. The former Prime Minister stands dignified in a blue pinstriped suit while soldiers surround him. A Peugeot 403, its model number clearly visible, waits ominously in the background near traditional houses that place the scene in the village of Lodja. This vehicle would become infamous – footage of Lumumba and two of his comrades being beaten in its backseat would be broadcast as a public humiliation before their torture and ultimate elimination.

Having lost his position and protection, Lumumba had tried to flee to Stanleyville where his supporters remained strong. But here, in this small village, his journey was cut short. The painting’s peaceful rural setting contrasts sharply with the reality it depicts. As in previous works, TKM annotates his painting, simply stating “ARRESTATION A LODJA,” letting the stark scene speak for itself.

The soldiers’ red berets identify them as part of the forces loyal to Mobutu, who had seized power with Western backing. Their presence here, far from the capital, shows how thoroughly the net had closed around Lumumba. His calm demeanor in the painting betrays nothing of what lies ahead, but the color has returned to TKM’s palette – this is no longer about political conflicts, but about life and death.

The Last Night: A Historic Death

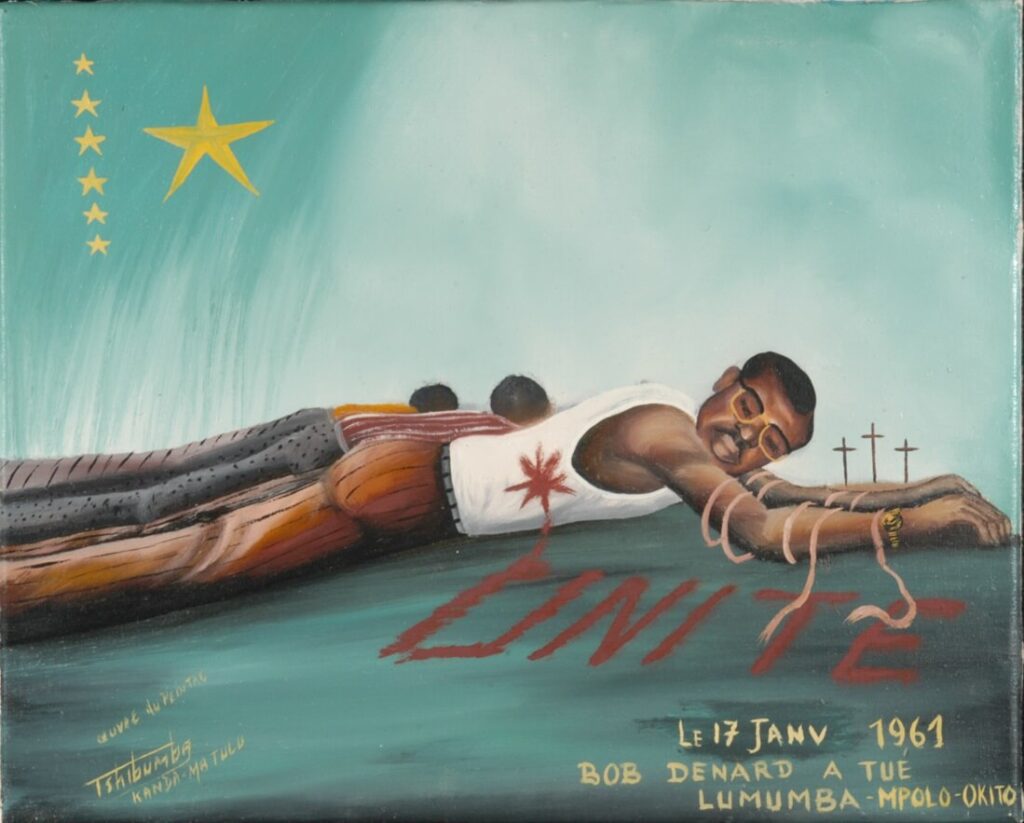

TKM’s haunting final painting leaves no room for the rumors and denials that would surround Lumumba’s fate for decades. Against a turquoise night sky lit by stars, we see Lumumba’s bound body, still wearing his signature glasses, lying beside his fallen comrades Mpolo and Okito. A single bullet wound marks his white undershirt, and from his blood flows the word “UNITE” – a final message that even in death, Lumumba’s dream of unity could not be silenced. The artist’s inscription states plainly: “LE 17 JANV 1961 BOB DENARD A TUE LUMUMBA-MPOLO-OKITO.”

After torture and public humiliation, Lumumba and his companions were driven to a remote location where Belgian officials and their Congolese allies carried out their execution. In a final act of colonial erasure, they dissolved the bodies in acid, keeping only Lumumba’s tooth as a grotesque trophy. For sixty years, while some claimed he had escaped, while others whispered different versions of his end, this tooth remained in Belgium – a silent witness to the truth. Its return in 2022 finally allowed Congo to close this chapter of its history, though TKM’s painting reminds us that Lumumba’s last message – unity – still resonates across the decades.

Conclusion

Lumumba’s voice terrified the colonial powers not because he called for violence, but because he wielded something far more potent – truth. Through TKM’s paintings, we’ve traced the journey of a man who rose from mine worker to Prime Minister through the sheer force of his intellect and character. His greatest weapon was his ability to articulate the reality of colonial exploitation in the colonizers’ own language, to expose their contradictions using their own logic. When he spoke, whether to brewery customers or to King Baudouin himself, people listened. This made him dangerous in a way armies could not match.

What we see through these artworks is more than just the tragic story of a leader’s assassination – it’s a testament to the power of words and dignity in the face of overwhelming force. Belgium and its allies could torture him, humiliate him, dissolve his body in acid, even keep his tooth as a trophy for sixty years. But they could not silence what he stood for. Today, 64 years after his death, Lumumba’s story remains shamefully undertold in international history. Yet his vision of true independence, of African dignity and self-determination, resonates more powerfully than ever.

Through TKM’s remarkable paintings, we’ve attempted to preserve not just what happened to Lumumba, but what he meant – to Congo, to Africa, and to all who dream of freedom. His story deserves to be known, studied, and remembered, not just as a martyred hero of Congo, but as a voice for human dignity everywhere. In his uncompromising pursuit of truth and justice, in his refusal to accept anything less than real independence, Lumumba left us a legacy that no amount of violence could erase.

Comments