Masks are humanity’s silent storytellers—universal symbols of the sacred, the communal, and the unseen. From the ancestral katsina of the Hopi to the ritual Topeng of Bali, they transcend borders, binding cultures to their histories and cosmologies. Yet, few traditions capture this spiritual depth as vividly as the masks of the Congo. For the Kuba, Luba, Songye, or Pende peoples, these are not mere artifacts but living entities: mediators of justice, vessels of ancestral wisdom, and essential threads in the fabric of community life.

It is a bitter irony, then, that those who once dismissed these traditions as “primitive” became their most ardent collectors. Missionaries preached salvation while pocketing sacred masks; colonial officers lectured on morality as they looted royal regalia. The very societies deemed in need of “civilizing” had perfected art forms that Europe could scarcely comprehend—masks encoding law, philosophy, and cosmology in wood and pigment. Yet these masterpieces were only deemed worthy of admiration once they were displaced, stripped of meaning, and rebranded as “Primitive art” in foreign halls.

Today, as museums debate the ethics of their holdings, the masks whisper a subversive truth: true civilization is not measured by conquest but by the ability to honor the sacred in others. Congo’s masks endure, not as relics of a frozen past, but as mirrors reflecting the paradox of a world that plundered beauty while claiming to enlighten it.

Masks of the Congo: Living Vessels of Ancestral Power and Cultural Identity

To see Congolese masks only as art is to mistake a heartbeat for an echo—failing to recognize their living essence. These masks are not static artifacts; they are living forces. Carved from sacred woods and infused with ancestral breath, they come alive in dance. Their role is not to decorate walls but to mediate, teach, heal, and transform.

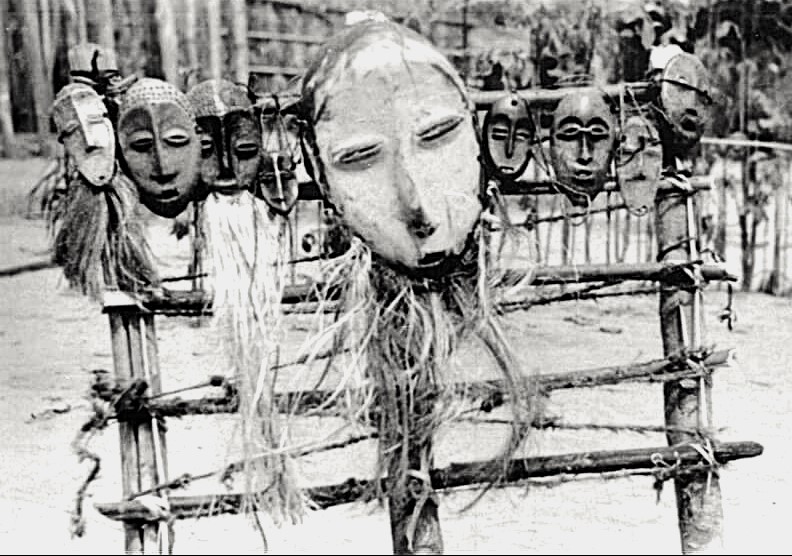

Take the Idimu mask, its stark features framed by a raffia beard. For the Lega people, this mask is not an adornment but a testament to wisdom. Only those who ascend through the Bwami society’s rigorous initiations earn the right to wear it, gaining deeper insight with each level. The Idimu becomes a moral compass, its presence enforcing social codes, resolving disputes, and binding the community to ancestral teachings. To possess such a mask is not a privilege, but a lifelong responsibility requiring ethical rigor.

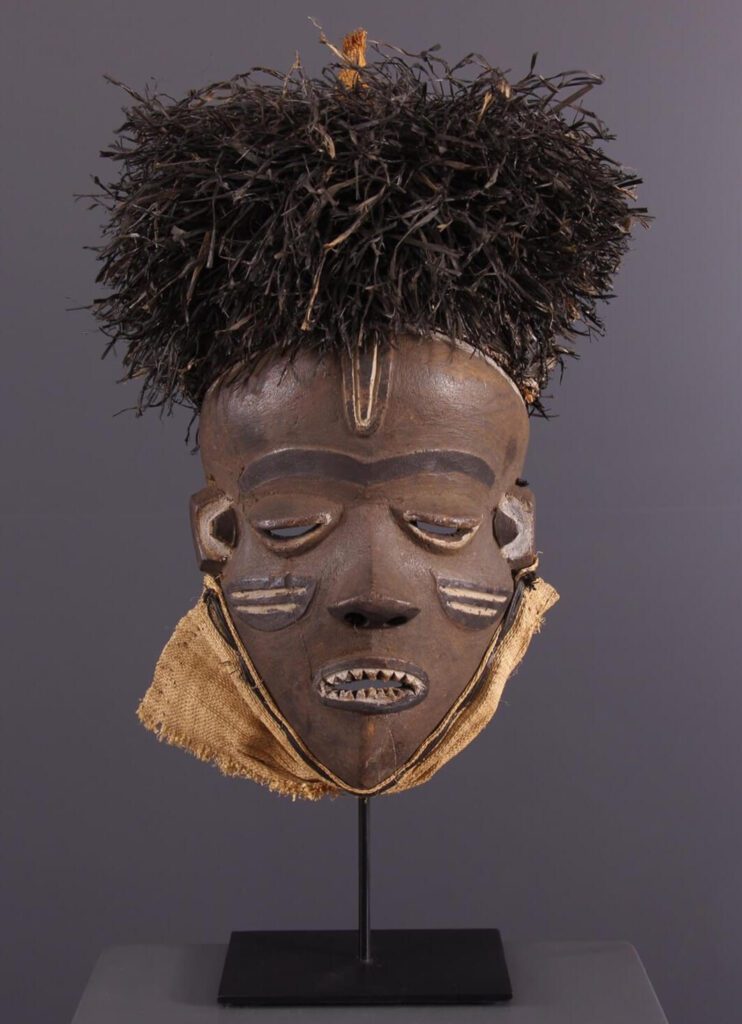

Or consider the Songye Kifwebe, its striated grooves echoing the ridges of the earth. In the Bwadi society, this mask is a guardian of balance. The striking geometry of the male masks embodies strength, while the softer, white-painted female versions symbolize harmony. Together, they summon cosmic forces to restore order in times of crisis, ensuring equilibrium in the community. These masks do not merely perform; they intervene, actively shaping the balance between chaos and stability.

No tradition exemplifies this narrative power more vividly than the Kuba people’s masks, breathing life into an ancient creation myth. At the heart of this epic lies a trio of characters: Ngaady a Mwaash, the founding queen, her face painted with tears of sorrow and resilience; Bwoom, the commoner, his bulbous forehead and brass-covered visage symbolizing the people’s defiance; and Mwaash aMbooy, the regal king, adorned with cowrie shells and beads that shimmer like stars. Together, they reenact the clash between royalty and commoners, a cosmic struggle for balance in Kuba society.

Even the Pende Mbuya mask, with its delicate curves and downcast eyes, carries quiet yet subversive power. Carved to represent ancestral spirits, it dances during Giphogo ceremonies, embodying both judge and jester. With a tilt of its head, it mocks arrogance; with a sudden leap, it startles the complacent. The Mbuya does not simply entertain—it critiques, corrects, and humbles, ensuring no individual rises above the collective.

The irony lies in the contrast: European colonizers, who claimed to bring “order” and “morality,” failed to recognize the sophisticated governance encoded in these masks. While Victorian societies jailed dissenters, Congolese masks resolved conflicts through ritual. While European churches preached sin, the Bwami society taught ethics through embodied art. The masks were not primitive—they were precise, their functions as nuanced as any legal code.

The Shadow of Colonialism: When Sacred Masks Became Silent Prisoners

To witness a Congolese mask in a European museum is to encounter a paradox: an object of profound spiritual vitality confined behind glass, labeled with clinical detachment. These masks, once dynamic forces of community life, were severed from their purpose by colonial hands that claimed to “enlighten” the very cultures they plundered. Missionaries, who preached the salvation of “heathen” souls, often doubled as cultural looters, pressuring communities to surrender masks they deemed “idols”—only to sell them abroad as exotic trophies. Colonial officers, meanwhile, displayed stolen regalia in their parlors as proof of conquest, oblivious to the irony: they had reduced living emblems of law and cosmology to decor.

The Kuba Mwaash aMbooy mask, a symbol of kingship, found itself trapped in a Brussels museum, its cowrie shells dulled under electric lights. The Songye kifwebe, designed to mediate cosmic balance, became a curio in a Parisian collector’s cabinet. Stripped of dance, drum, and ritual, the masks were rendered mute—a spiritual lobotomy performed in the name of “civilization.”

Yet the greatest violence lay not in theft alone, but in the erasure of meaning. Colonial museums labeled these masks “primitive art,” divorcing them from the ethical frameworks they embodied. What Europeans dismissed as “superstition” was, in fact, a sophisticated system of governance: the Lega Idimu enforced social codes, the Pende Mbuya humbled tyrants, and the Kuba trio (Ngaady a Mwaash, Bwoom, and Mwaash aMbooy) enacted myths that sustained societal balance. The colonizers, who claimed to bring order, had dismantled a world where masks were the law.

Today, these masks whisper an undeniable truth from their glass cages: the so-called “civilizers” were the true vandals. They who preached morality stole the moral guides of others; they who claimed to uplift cultures severed their roots. But the story does not end here. As Congolese communities reclaim their heritage, these masks await liberation—not merely to return home, but to live again.

The Path to Cultural Restoration: From Stolen Relics to Living Heritage

The journey to restore Congolese masks is not merely about physical repatriation—it is a battle to reignite their spiritual and cultural essence. In 2022, Belgium’s King Philippe made a symbolic gesture by returning a single Kuba mask, looted during his ancestor Leopold II’s brutal reign, to the Democratic Republic of Congo. While hailed as progress, many Congolese saw it as a hollow act. One mask could not compensate for the thousands stolen, nor heal the deep cultural wounds left by colonialism.

The question lingers: When a people reclaim what was taken from them, is it theft or justice? A similar debate arose in 2009 when two Chinese zodiac bronzes, looted during the Opium Wars, were auctioned in Paris. A Chinese bidder won them for €31 million but refused to pay, calling the sale a “moral crime.” Like Congo’s masks, the bronzes were prisoners of colonial history, their ownership contested by those who insist: Looted art cannot be “owned.”

For Congo, the stakes are even higher. Masks like the Lega Idimu or Kuba Mwaash aMbooy are not just artifacts; they are living symbols of cultural identity. They were created to be worn, to dance, and to teach. Yet Western institutions often justify keeping them through legal loopholes, citing provenance records written by colonizers or claiming to “preserve heritage” in climate-controlled vaults.

The contradiction is clear: the same powers that once looted these artifacts under the guise of a “civilizing mission” now call themselves “cultural stewards.” True preservation, however, means recognizing these masks as part of a living tradition—and returning them to the communities that gave them meaning.

Conclusion

Let us speak plainly: the looting of Congo’s masks is not an isolated event—it is part of a larger pattern of cultural theft. The Benin Bronzes, plundered by British soldiers, remain in London. The sacred katsinam of the Hopi are auctioned in Paris. The ancestral remains of Indigenous Australians sit in storage in Berlin. Nefertiti, Egypt’s radiant queen, is displayed in a Berlin museum, her presence a symbol of colonial entitlement. The cycle is familiar: label a culture “primitive,” seize its heritage, then claim the right to define its legacy.

Western institutions often justify their possession of looted artifacts under the guise of preservation. They claim to protect these treasures “for humanity,” yet humanity, in their view, is conveniently centered in London, Brussels, and New York. How thoughtful of them to decide, on behalf of the world, where history should reside. True preservation, however, would mean restoring these objects to the communities that created them, where they continue to hold meaning beyond mere aesthetic value.

Despite displacement, these artifacts remain symbols of resilience. The Kuba Mwaash aMbooy still gleams, and the Songye kifwebe still holds its spiritual power. These masks are not relics of a lost world but living testaments to cultures that endure despite centuries of colonial erasure.

The path forward is clear: return Nefertiti to her Nile. Send the bronzes back to Benin. Let Congo’s masks dance again. Perhaps then, the guardians of “universal heritage” can finally prove they value justice as much as they claim to value history.

When will the “civilized” world finally learn from its past, rather than force others to relive it?

Comments