Introduction

In nearly every account of Congolese contemporary art history, one name appears again and again as its so-called starting point: Le Hangar in Lubumbashi. Hailed by many as the “first atelier for indigenous art” in the Belgian Congo, it’s often praised for pioneering a cultural awakening—allowing Congolese painters, for the first time, to be recognized as more than “naïve” folk artists. Yet, the very language used in these narratives—”indigenous,” “naïve,” “discovery”—unmasks a condescending perspective steeped in colonial bias.

To be sure, Le Hangar might have been the first officially sanctioned art studio in the Belgian Congo dedicated solely to Congolese creators, but it was also thoroughly governed by a paternalistic colonial system. It didn’t appear in an artistic vacuum. Congolese traditions of painting, carving, and sculpture long predated the Belgians—and indeed, there were other ateliers in the Congo that existed beyond the scope of colonial documentation. Still, much of the written history ties the evolution of Congolese art to a white mentor who supposedly unlocked the hidden potential of “exotic” African subjects.

In reality, this relationship was anything but egalitarian. Under the leadership of Pierre Romain Desfosses—an officer of the same regime that brutally exploited millions of Congolese—Le Hangar was subject to colonial funding and control. While contemporaries like Ben Enwonwu from Nigeria and Latin American artists freely explored their artistic visions on the global stage, Congolese artists at Le Hangar were restricted to producing works that satisfied colonial fantasies.

This essay is thus provocative by design: it seeks to question the over-glorified accounts of Le Hangar, to show how it functioned more as a colonial propaganda tool than a liberating art space. By examining not just the atelier’s operations but also its broader context—both colonial and global—we reveal how the celebration of “authentic” African art served to mask ongoing cultural oppression. The story of Le Hangar is not merely about art; it’s about power, control, and the colonial machinery that turned even creativity into a tool of oppression.

A Stage Set by Colonial Violence

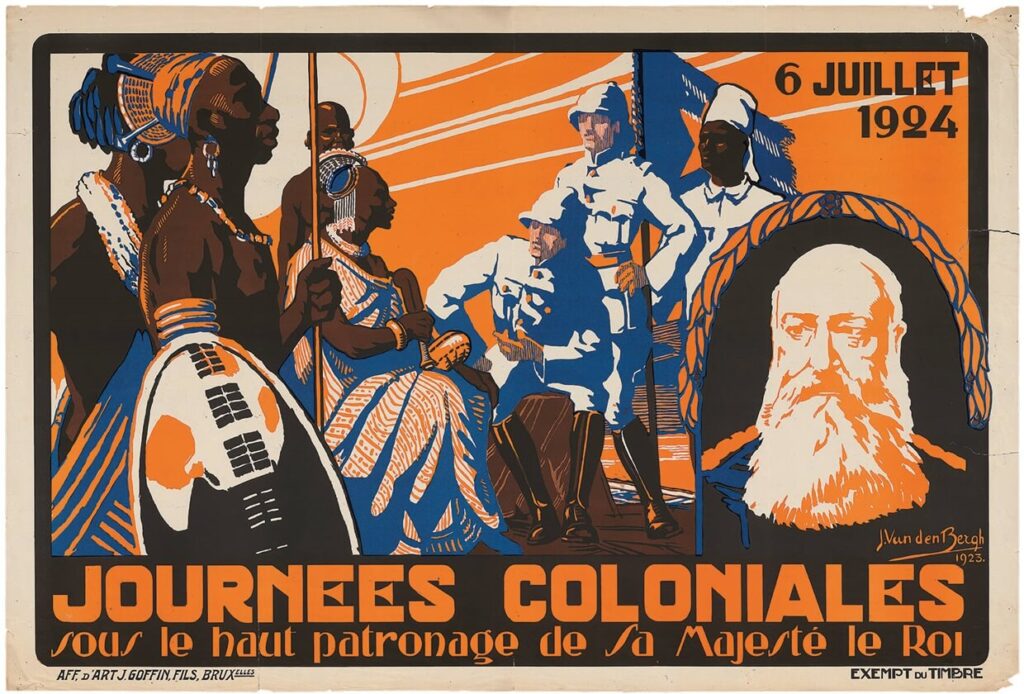

As the 1940s drew to a close, Belgium was desperately trying to rewrite its colonial narrative from one of brutality to benevolence. The shadow of King Leopold II’s regime loomed large – a period that had seen millions of Congolese killed, mutilated, and enslaved. The infamous photographs of Congolese children with severed hands had shocked the world, yet here was Belgium, mere decades later, positioning itself as a custodian of African culture.

This transformation wasn’t spontaneous. By 1947, growing international scrutiny and the first stirrings of independence movements across Africa forced Belgium into a sophisticated public relations campaign. The Royal Museum for Central Africa in Brussels – itself a monument to colonial plunder – suddenly “discovered” that its 250,000 looted objects weren’t just colonial trophies but “art” requiring Belgian protection. Between 1947 and 1958, under director Frans Olbrechts, these artifacts were carefully rebranded from ethnographic specimens to “Congolese art,” creating a new narrative of cultural guardianship.

The shift from “civilizing mission” to “cultural protection” was a masterful sleight of hand. While Belgium spoke of preserving indigenous traditions, its policies continued to systematically dismantle Congolese social and cultural structures. Colonial authorities presented themselves as saviors of traditions they were actively working to erase. As prominent Belgian journalist Fernand Demany declared in 1955, without a hint of irony, “we must save indigenous art” – conveniently forgetting who had endangered it in the first place.

It was in this context of colonial image rehabilitation that Le Hangar emerged. The atelier became a perfect showcase for Belgium’s new role as “protector” of Congolese culture. Here was tangible “proof” of Belgian benevolence – a space where African artists could supposedly flourish under European guidance. The fact that this guidance came from a colonial officer, funded by colonial administration, seemed to raise no eyebrows in contemporary accounts.

The Painted Façade of Cultural Benevolence

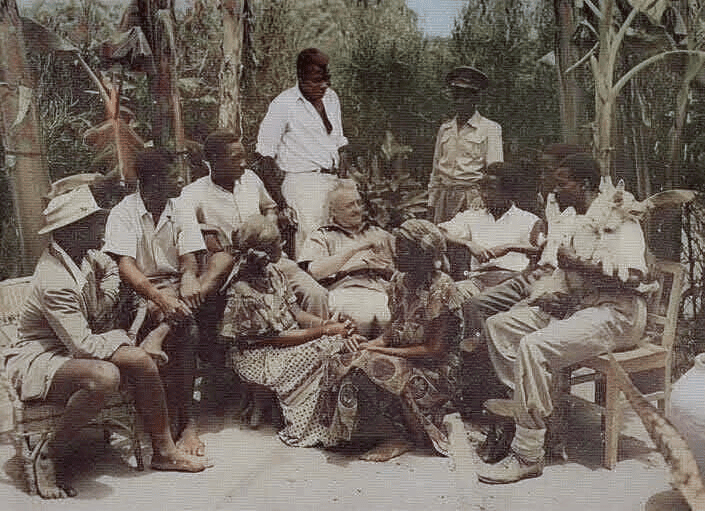

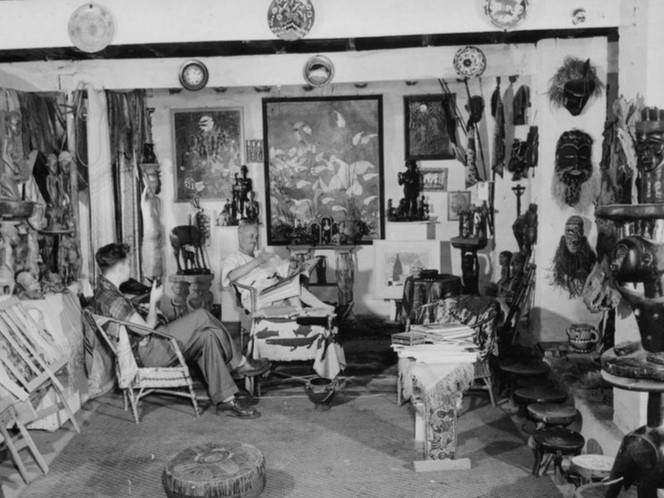

In 1947, Pierre Romain Desfosses, a self-taught painter with a particular interest in fauna and flora, established what would become one of the most celebrated colonial art institutions in Belgian Congo. Contemporary accounts paint him as a visionary educator who encouraged artists “to sit under a tree” to find their “original black soul.” His frequent references to his students as “his children,” though presented as endearing in colonial literature, epitomized the paternalistic attitude inherent in colonial cultural institutions.

Behind this romantic narrative of artistic nurturing lay a calculated reality. The atelier, fully funded by the colonial administration, operated under a carefully constructed illusion of artistic freedom. While Desfosses claimed his students were free to create whatever they wished, the overwhelming focus on exotic fauna and flora tells a different story. The artwork produced at Le Hangar aligned suspiciously well with European expectations of what “authentic” African art should be – images that satisfied colonial fantasies without challenging colonial authority.

The physical space itself – a converted warehouse – embodied the industrial nature of this cultural production. Everything was organized to showcase Belgium’s new role as “protector” of indigenous art. The colonial press eagerly documented this “artistic sanctuary,” while carefully avoiding any mention of the power dynamics at play. Paintings were displayed in Belgian galleries and sold to European collectors as prime examples of “authentic” African expression, with profits flowing through colonial channels.

Marketing these works was a sophisticated operation. The colonial machine controlled every aspect: from production to exhibition, from sales to documentation. Artists’ technical brilliance was celebrated, but their artistic autonomy was strictly limited. Their works were presented as evidence of successful colonial guardianship rather than individual creative expression. Even the language used in exhibitions and publications reinforced colonial hierarchy – artists were consistently described as “pupils” or “students,” never as independent creators.

The success of this propaganda was remarkable. Le Hangar gained international recognition, with works purchased by prestigious institutions like New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Yet this recognition came at a price – the perpetuation of the myth that African artists needed European guidance to produce “legitimate” art. The artists’ own voices – their thoughts, aspirations, and true artistic visions – remain conspicuously absent from the historical record.

The Global Stage: A Study in Contrasts

During the same period that Le Hangar operated, artists from other formerly colonized regions were achieving international recognition on their own terms. Ben Enwonwu, the Nigerian artist, was making headlines in London not as a supervised “native talent,” but as an independent master merging African traditions with modernist techniques. Unlike the artists at Le Hangar, Enwonwu gave interviews, wrote about his artistic philosophy, and openly discussed his work’s political implications. He didn’t need a colonial officer to “discover” or interpret his talent.

In Latin America, artists were boldly confronting colonial legacies through their work. Tarsila do Amaral revolutionized Brazilian modern art by deliberately incorporating indigenous themes, creating the Anthropophagic movement that proudly “cannibalized” European artistic traditions. Frida Kahlo in Mexico was producing searing critiques of colonialism, gender, and identity – subjects that would have been unthinkable at Le Hangar. Emilio Pettoruti gained international recognition while maintaining his distinctive Argentine perspective. Their voices echo through history in interviews, letters, and manifestos, while the thoughts of Le Hangar’s artists remain buried.

The documentation tells its own story. While we have extensive writings, interviews, and personal statements from these artists, photographs of them working independently in their studios, and records of their artistic development, Le Hangar’s artists appear primarily in colonial photographs, always under supervision, their individual voices muted. When their work was discussed, it was invariably through the filter of Desfosses’s vision and colonial interpretation.

This contrast raises disturbing questions about Le Hangar’s true purpose. If artists from other formerly colonized regions could achieve international success without colonial “guidance,” why were Congolese artists supposedly in need of such supervision? If artists elsewhere could freely explore political and social themes, why were Le Hangar’s artists restricted to fauna and flora? The answer lies not in any lack of talent among Congolese artists, but in the colonial system’s determination to control and contain their expression.

Artists in the Shadow of Empire

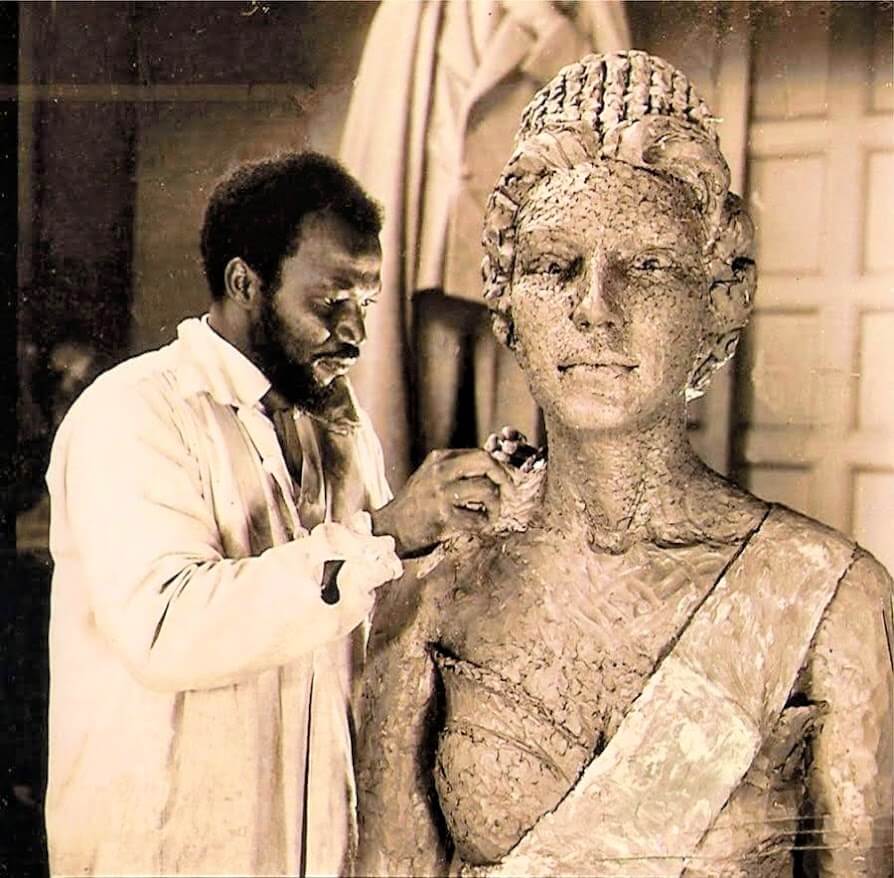

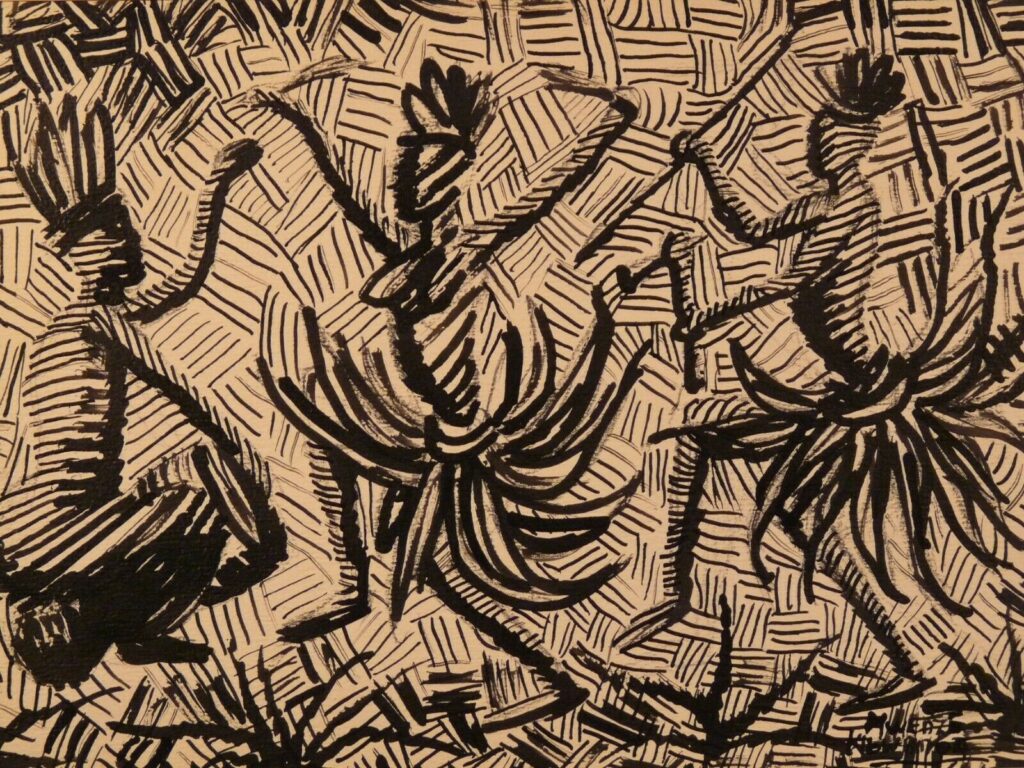

Despite the colonial constraints, several extraordinary artists emerged from Le Hangar, though their stories have been largely overshadowed by Desfosses’s carefully curated narrative. Pilipili Mulongoy developed intricate compositions that transformed the imposed subject matter of flora and fauna into mesmerizing patterns of light and movement. While his technical brilliance was celebrated in colonial exhibitions, his own thoughts about his art remain lost to history. His works now grace museums worldwide, yet we know more about what Desfosses thought of them than what Pilipili himself intended to express.

Mwenze Kibwanga’s journey particularly illustrates the colonial control over artistic expression. Beginning as a self-taught artist specializing in portraits and landscapes, he was compelled to adapt his style to meet colonial expectations. His innovative technique of small lines and dots, which became his signature style, emerged from this imposed transition. Colonial records praise his “natural talent,” yet they never document his own voice about this artistic evolution.

Bela Sara developed his own distinctive approach within the prescribed themes of Le Hangar. Like his fellow artists, his work was celebrated in colonial exhibitions, yet his own artistic philosophy and personal vision remain undocumented. The colonial archive preserves only the European interpretation of his work, leaving his own voice silenced.

The success of these artists is undeniable – their works were collected by prestigious institutions, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art, which purchased a hundred pieces from Le Hangar. Yet this international recognition came with a bitter irony: their art was marketed and sold through colonial channels, with profits and prestige largely benefiting the colonial system rather than the artists themselves. Their technical mastery shines through even within their restricted subject matter, leaving us to wonder what these same gifted hands might have created had they been truly free to explore any subject, any theme, any artistic vision they chose.

Conclusion

The story of Le Hangar reveals a sophisticated mechanism of colonial control masked as cultural patronage. While celebrated in historical accounts as a cradle of modern Congolese art, closer examination exposes it as a carefully orchestrated propaganda tool in Belgium’s effort to rebrand its colonial image. The contrast between Le Hangar’s artists and their global contemporaries is telling – while Ben Enwonwu, Tarsila do Amaral, and others freely explored their artistic visions, Congolese talents were confined to producing works that satisfied colonial expectations.

The tragic irony of Le Hangar lies not in the quality of art produced – the technical brilliance of Pilipili Mulongoy, Mwenze Kibwanga, Bela Sara, and others is undeniable. Rather, it lies in the systematic suppression of their individual voices and creative freedom. While their works hung in prestigious galleries and museums, their own thoughts, aspirations, and artistic philosophies were buried under layers of colonial narrative.

The legacy of Le Hangar extends beyond its immediate historical context. It exemplifies how cultural institutions can serve as tools of political control, how art can be both a means of expression and suppression. The absence of the artists’ voices in historical records speaks volumes about colonial power structures that continue to influence how African art is perceived and presented.

As we critically reexamine this history, we must look beyond the romantic narrative of artistic “discovery” and “nurturing” to see Le Hangar for what it was – a colonial factory producing “authentic” African art that carefully avoided challenging colonial authority. The true testament to the artists’ genius lies not in their ability to meet colonial expectations, but in how their creativity and technical mastery shone through despite these constraints.

Comments