The history of Africa’s cultural influence around the globe is as vital and persistent as a heartbeat. We often trace the journey of Congolese rumba. This genre is so central to the cultural narrative of Congo that it sometimes eclipses other artistic expressions. While this focus is a source of great pride, it might also limit our view of that creativity.

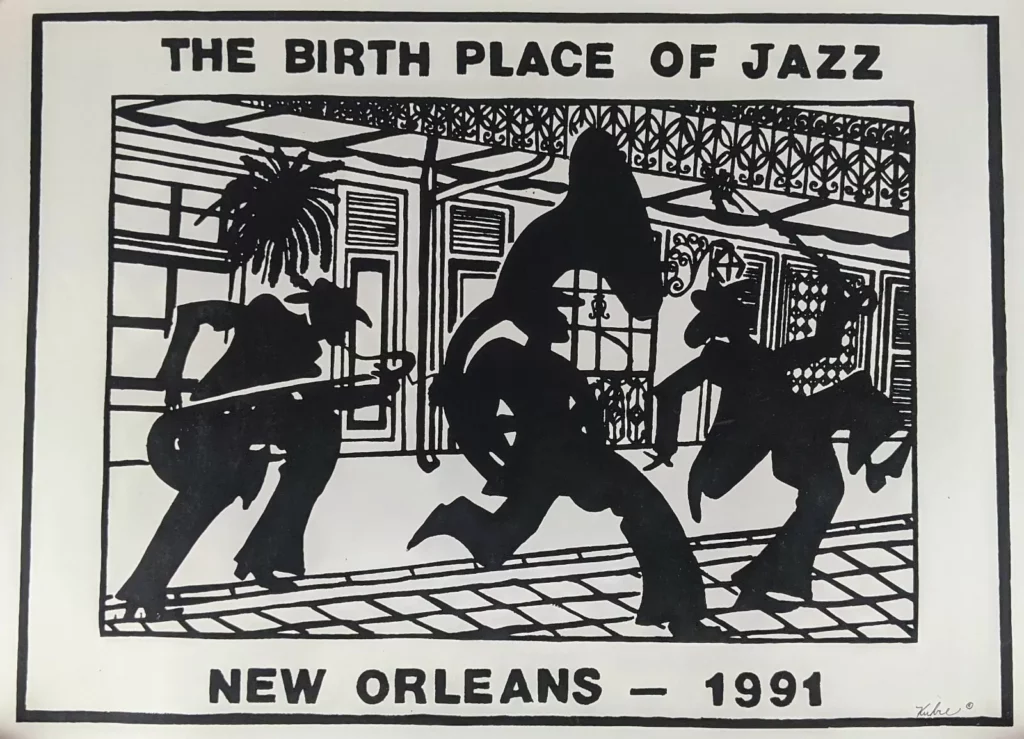

Congolese culture is far from one-dimensional. Its influence pulses across continents, impacting the music of Cuba and the vibrant landscape of New Orleans. Congo Square proves that culture is not a garment to be stripped away, but the heartbeat of a people. It can be muffled, but it cannot be stopped without extinguishing life itself. In this small patch of New Orleans, oppression tried to silence that pulse. Instead, the pressure forced that heart to beat stronger, developing new rhythms to survive. This space birthed jazz and the Mardi Gras Indians. These are testaments to how culture is the ultimate act of survival, the very thing that keeps us human when everything else tries to destroy us.

The Birth of Congo Square

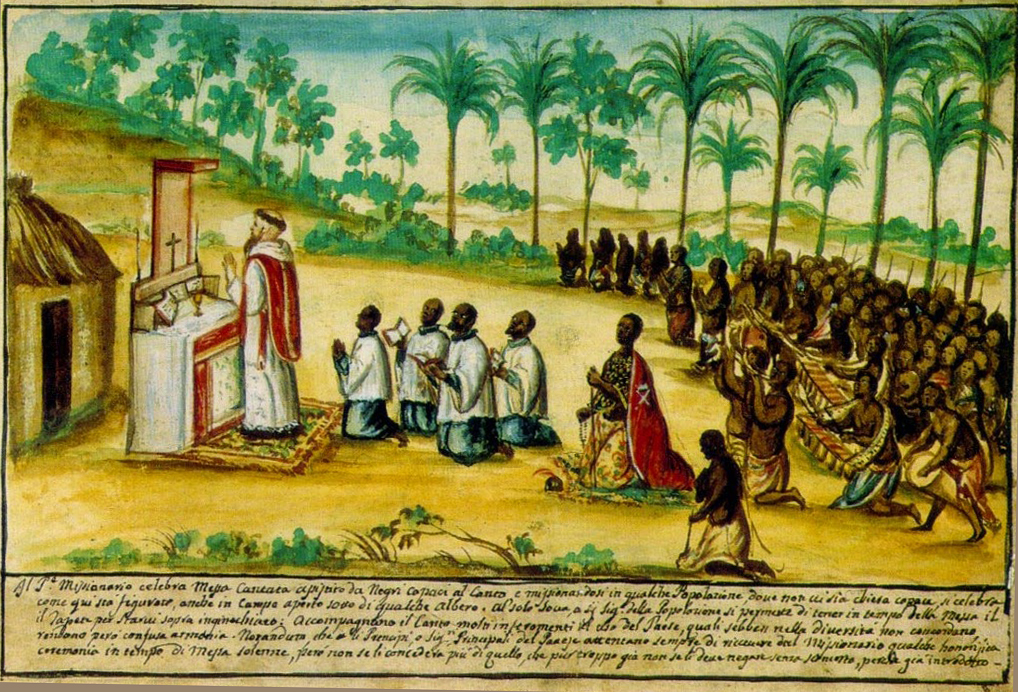

In the early eighteenth century, amidst the brutality of the slave trade, a unique space emerged in New Orleans. It would later become known as Congo Square. Initially called “Place des Nègres,” its name reflects the segregation of the time. The French Code Noir mandated that enslaved people observe Catholic Sundays. Enslaved Africans seized this requirement, transforming it into a sanctuary where their cultural pulse could beat openly.

Here, they asserted their humanity. The square became a vital marketplace where they sold goods, achieving a degree of economic autonomy. It was also a place of profound cultural affirmation, though always under the watchful eye of white authorities.

The strong presence of Kongolese people in New Orleans stemmed from historical decisions made centuries earlier. When King Afonso I of the Kongo Kingdom embraced Christianity and established diplomatic relations with European powers in the early sixteenth century, he unwittingly influenced the fate of his people generations later. Slave traders came to prefer capturing people from the Kongo Kingdom, viewing them as “more civilized” due to their Christian background. A terrible prejudice born of European arrogance. Yet this cruel preference had an unexpected result: it concentrated enough Kongolese people in New Orleans to maintain their cultural practices, creating a critical mass that would prove impossible to silence.

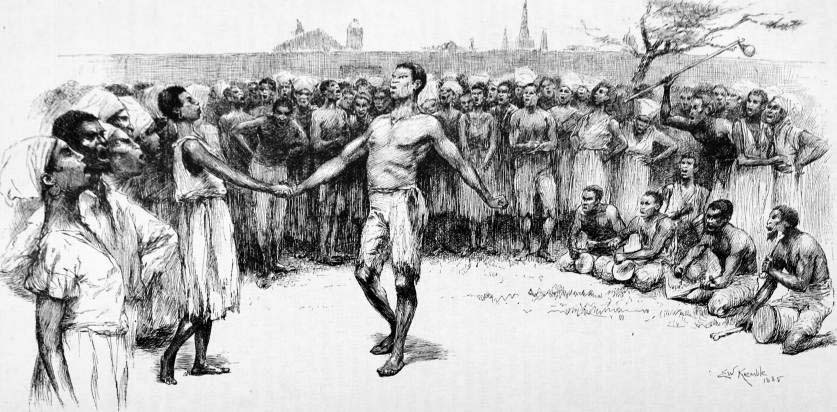

The Sunday gatherings faced constant threats. White residents complained about the “noise” and “savage displays.” Governors issued restrictions. In 1856, authorities banned drums and horns entirely. Yet each restriction only revealed the futility of trying to cage human expression. When drums were forbidden, rhythm found new vessels: bamboo sticks, hand claps, the human body itself. Benjamin Latrobe, approaching the square in 1819, first thought he heard horses trampling on wooden floors. It was actually hundreds of feet dancing, creating thunder that rolled through the city.

Observers described astonishing scenes: dancers in “oriental and Indian dress with Turkish turbans,” women in silk and muslin who “hardly moved their feet” while making “the most wonderful bending gestures,” all moving to music that mixed African rhythms with unexpected influences. What outsiders saw as chaos was actually sophisticated cultural preservation. Every gesture carried meaning, every rhythm told a story, every gathering strengthened bonds that slavery sought to break.

When Cultures Meet and Merge

Congo Square became more than a gathering place. it evolved into a cultural crucible where an extraordinary alchemy occurred. Here, enslaved Africans encountered Native Americans who had established trading networks in the area, and both groups discovered something profound: they shared not just a marketplace, but a common experience of dispossession.

The Choctaw traders who brought herbs and crafts to sell recognized something familiar in the Kongolese ceremonies. The circular dance formations echoed their own rituals. The sacred role of drums resonated with their traditions. Both peoples understood what it meant to have their children torn away, their languages forbidden, their gods declared false. This recognition sparked more than sympathy; it ignited creative fusion.

As trust grew, so did mutual support. Native Americans provided shelter to runaways, knowledge of escape routes through their territories, and spiritual solidarity. In return, African rhythms began conversing with indigenous melodies, Kongolese dance movements incorporated Native American gestures, and entirely new forms of expression emerged that neither culture could have created alone. It was a demonstration that shared struggle could forge bonds stronger than blood.

The Evolution of Carnival

When authorities finally succeeded in quieting Congo Square in the years leading up to the Civil War, they celebrated too soon. The culture had not died. It had simply gone underground, flowing through the city’s veins like a hidden river. The community bonds forged in those Sunday gatherings proved too powerful to suppress. Like water finding cracks in a dam, these traditions seeped into every corner of the city’s life.

The culture emerged transformed in Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs. These organizations grew naturally from the community structures developed during the Congo Square era. These were not just insurance societies or social groups. They were vessels carrying forward ancient rhythms and communal practices. Through these clubs, the resilience practiced in Congo Square found new life. The second lines that still dance through New Orleans streets today echo those Sunday gatherings, proving that culture suppressed only grows stronger.

The most spectacular proof of cultural invincibility appeared in the Mardi Gras Indians (Black Masking Indians). Their elaborate costumes became walking declarations that African and Native cultures had not just survived but had married and multiplied. Intricate beadwork blends African techniques with Native American ceremonial designs. Their art tells the story of two peoples who found kinship in struggle. Their music carries forward African call-and-response patterns and Native American chants. Their fierce protection of their flags echoes ancient traditions of defending sacred symbols. When they parade through the streets, they are proving that the spirit born in Congo Square could never be contained.

Jazz: The Voice of Congo Square

Jazz became the ultimate proof that oppression breeds innovation. Every attempt to silence African rhythms had only taught them to speak new languages. The polyrhythms that once thundered through Congo Square learned to whisper through brass instruments. Call-and-response patterns found new voice in improvisation. The complex layering of rhythms evolved into the syncopation that would define a new musical era.

This was not just musical evolution. It was cultural alchemy. The “Bamboula” and “Calinda” dances that animated Congo Square carried specific rhythms. The distinct three-beat pattern known as the “tresillo” became the fundamental heartbeat of jazz. The spontaneous musical dialogues of those Sunday gatherings became the foundation of improvisation. European instruments became vessels for African rhythmic sophistication. The blues scales carried the sorrow and resilience of centuries.

What emerged was not African music or European music. It was something entirely new, born from pressure and struggle, that would soon seduce the very people who had tried to suppress it. Jazz conquered the world not despite its origins in oppression but because of them. It carried within its rhythms the unstoppable force of cultures that refused to die. When Louis Armstrong’s trumpet sang or Jelly Roll Morton’s piano danced, they were channeling the spirits of Congo Square. They proved that culture flows forward like a river, gathering strength from every obstacle it encounters.

Conclusion

The story of Congo Square is a powerful reminder that cultures endure, evolve, and enrich the world, even in the face of unimaginable suffering. It is the essential proof of life and the ultimate form of resistance. It is the heartbeat that sustains humanity against the forces of dehumanization. The enslaved people who gathered in that dusty square were doing more than dancing. They were demanding recognition of their humanity. They could not know that their rhythms would echo through centuries, birthing a music that defines America itself.

The transatlantic slave trade is not just a chapter in diaspora history. It is an integral part of African history. It shows how African culture did not end at the water’s edge but evolved, its pulse spreading to influence the entire world. The story of Congo Square reveals that attempts to suppress culture only amplify its essential nature. When different peoples meet in the crucible of shared struggle, their traditions synchronize and strengthen.

They remind us that true cultural vitality comes not from purity or isolation, but from the creative collision of traditions. No amount of oppression can stop this fundamental human truth. We will create, we will celebrate, we will endure. Our culture is the rhythm that moves us forward, an unstoppable pulse carrying the stories of all who contribute to the beat. The lesson of Congo Square reaches far beyond New Orleans. It shows us that the human heart, and the culture it sustains, will always find a way to beat freely.

Comments