Introduction

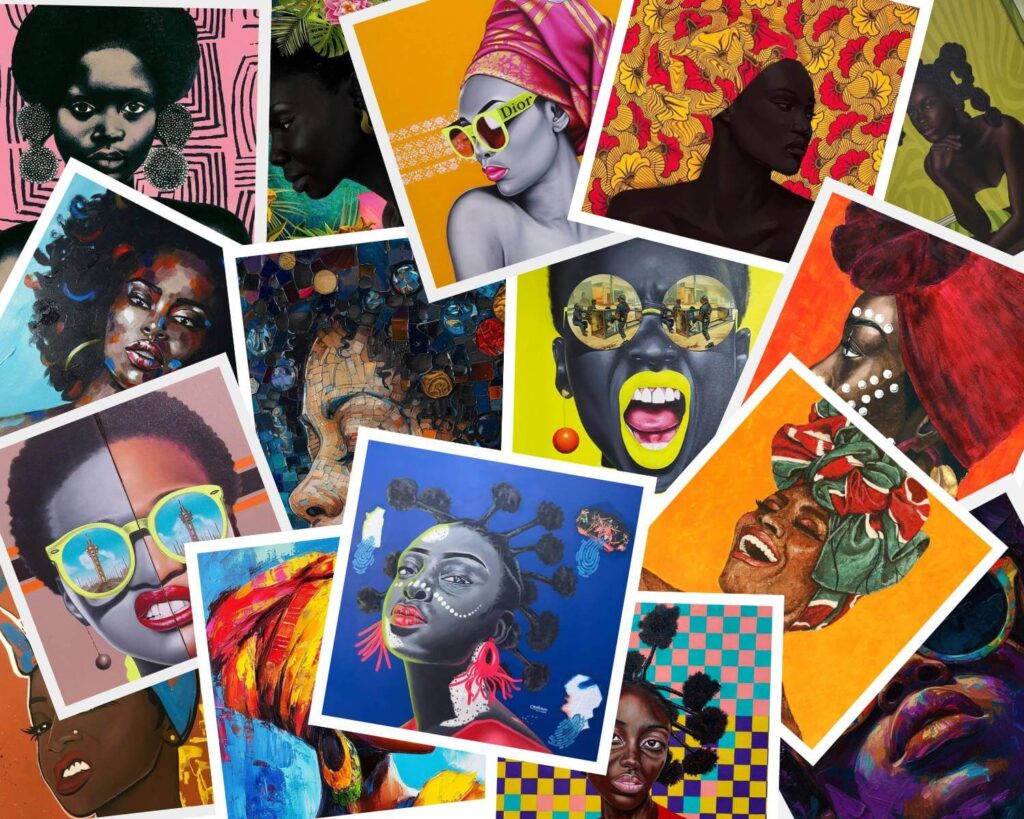

Let’s be honest: a huge part of the African art market right now is broken. Walk into any gallery catering to foreign buyers in a major African city, and you’ll see the same thing: wall after wall of colorful, stereotypical portraits of African women. These paintings aren’t celebrating culture; they’re commodifying it. They reduce incredibly diverse cultures to a single, exoticized cliché.

This isn’t a new complaint. Famous African artists have been calling this out for years. But Western galleries and buyers, eager for a piece of “Africa,” keep buying it up. They’re not just buying a pretty picture; they’re perpetuating a cycle that dates back to colonial-era photography, where African women were treated as objects of curiosity.

But here’s the worst part: many of these best-selling artworks aren’t even original. They’re direct, traced copies of photos stolen from the internet. Artists are printing images onto canvases, painting over them, and selling the forgeries for thousands of dollars. And the galleries? They’re letting it happen because it sells.

This article argues that breaking this cycle requires conscious effort from all market participants. By understanding the historical roots, the modern economic drivers, and the concrete evidence of plagiarism, art consumers can make ethical choices that support genuine artistic expression. We will explore the role of galleries in perpetuating this trend and conclude with a practical guide for championing a more authentic and respectful art market.

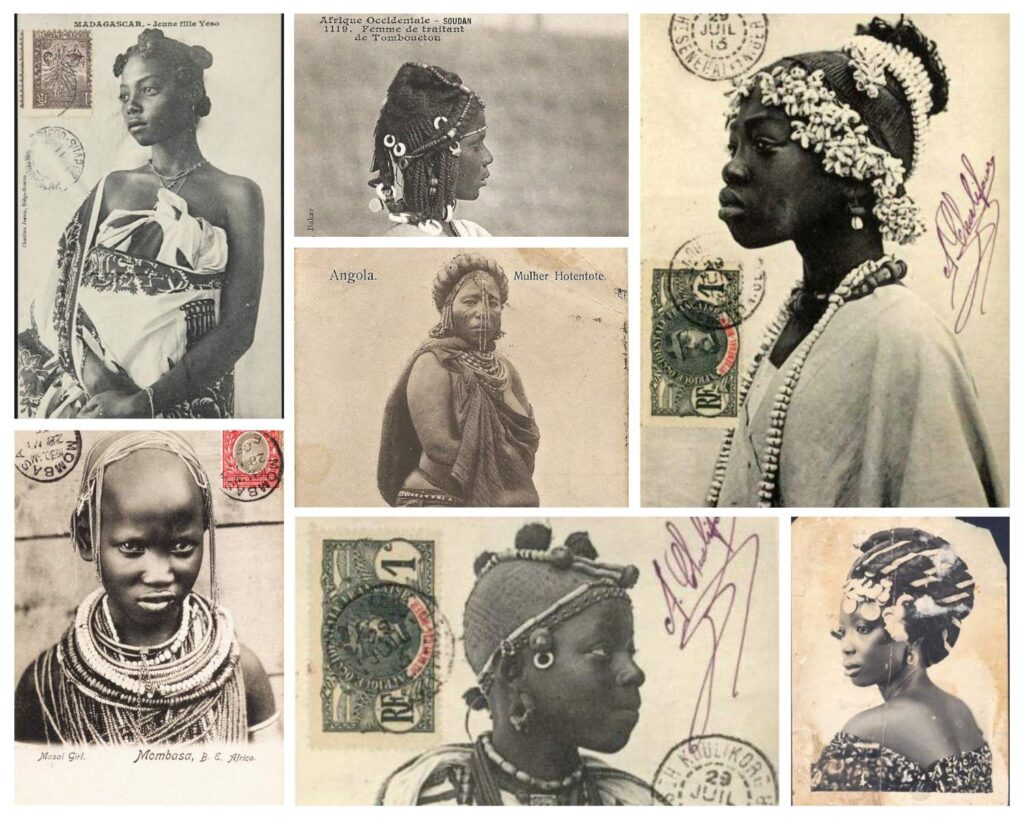

A Legacy of Objectification: From Colonial Lens to Modern Cliché

The origins of stereotypical portraits of African women are deeply rooted in colonial photography. During that era, European photographers systematically portrayed African women as exotic specimens, reinforcing racial hierarchies and dehumanizing their subjects. These images were not created for Africans; they were designed to satisfy the curiosity and fantasies of a European audience, presenting a simplistic and derogatory view of diverse cultures.

As scholar Elizabeth Harney notes, “The exoticization of African women in colonial photography was a form of cultural appropriation, as it used images of African women to satisfy the curiosity and fantasies of Europeans.”

Tragically, this practice has not been consigned to history. Many contemporary portraits simply repackage this colonial gaze, continuing to exoticize and objectify African women. They reduce rich, complex identities to simplistic stereotypes, perpetuating the idea that African women are objects of curiosity rather than individuals with agency and depth.

“The exoticization of African women in colonial photography was a form of cultural appropriation, as it used images of African women to satisfy the curiosity and fantasies of Europeans.” – Elizabeth Harney.

The Market Machine: How Profit-Driven Galleries Perpetuate the Cycle

This trend persists because there is a market for it, and commercial galleries—particularly those catering to foreign buyers and expats—are often the engine. In cities like Kinshasa, the dominant market force can be European buyers drawn to a specific, stereotypical aesthetic. Galleries, responding to this demand, often prioritize these commercially viable, trend-driven pieces over genuine, original works. This creates a feedback loop: artists need to sell to survive, so they produce what sells, and galleries continue to supply it.

One might ask, why should they do anything else? They are profiting from it, and it is selling. This system is not likely to change until there are tangible consequences, not only for the artists but also for the galleries that enable and profit from this trade. The tragic irony is that every serious gallery director or curator possesses the skill to distinguish between plagiarism and original work. In fact, some of the women’s faces have been used so frequently they have become familiar to everyone in the local art scene, turning a blind eye into a conscious choice.

This is not necessarily a moral failing of every individual artist, but a systemic issue. We see two types of artists in this ecosystem: those who solely produce plagiarism. I’m not even sure if they know how to paint beyond adding decorative colors to stolen photographs. And talented artists who used to create authentic work but have gradually moved into producing these portraits because they sell. The latter is perhaps the greater tragedy of a corrupted market.

As the legendary artist El Anatsui stated, “There is a constant struggle between staying true to my artistic vision and making ends meet. It’s not always easy to find a balance between the two.” This pressure is real, but it does not excuse the galleries who exploit it.

The ultimate victims are the buyers who trust the expertise and reputation of their galleries, only to be sold a scam. They invest their money and passion into a piece they believe is original and meaningful, unaware they are purchasing a well-framed forgery of a digital file.

By prioritizing sales over authenticity, these galleries contribute to a perverted art market. African artists are pressured to produce works that appeal to foreign buyers’ preconceptions rather than works that reflect their true cultural heritage and personal vision. This dynamic undermines the integrity of African art and reduces its incredible diversity to a set of superficial, exotic traits.

“There is a constant struggle between staying true to my artistic vision and making ends meet. It’s not always easy to find a balance between the two.” – El Anatsui.

The Evidence: Exposing a Culture of Copy-Paste Art

The most damning aspect of this trend is not just the exoticization, but the rampant plagiarism and outright fraud that fuels it. A significant portion of these modern artworks are not genuine expressions of creativity but are technical reproductions sourced directly from the internet.

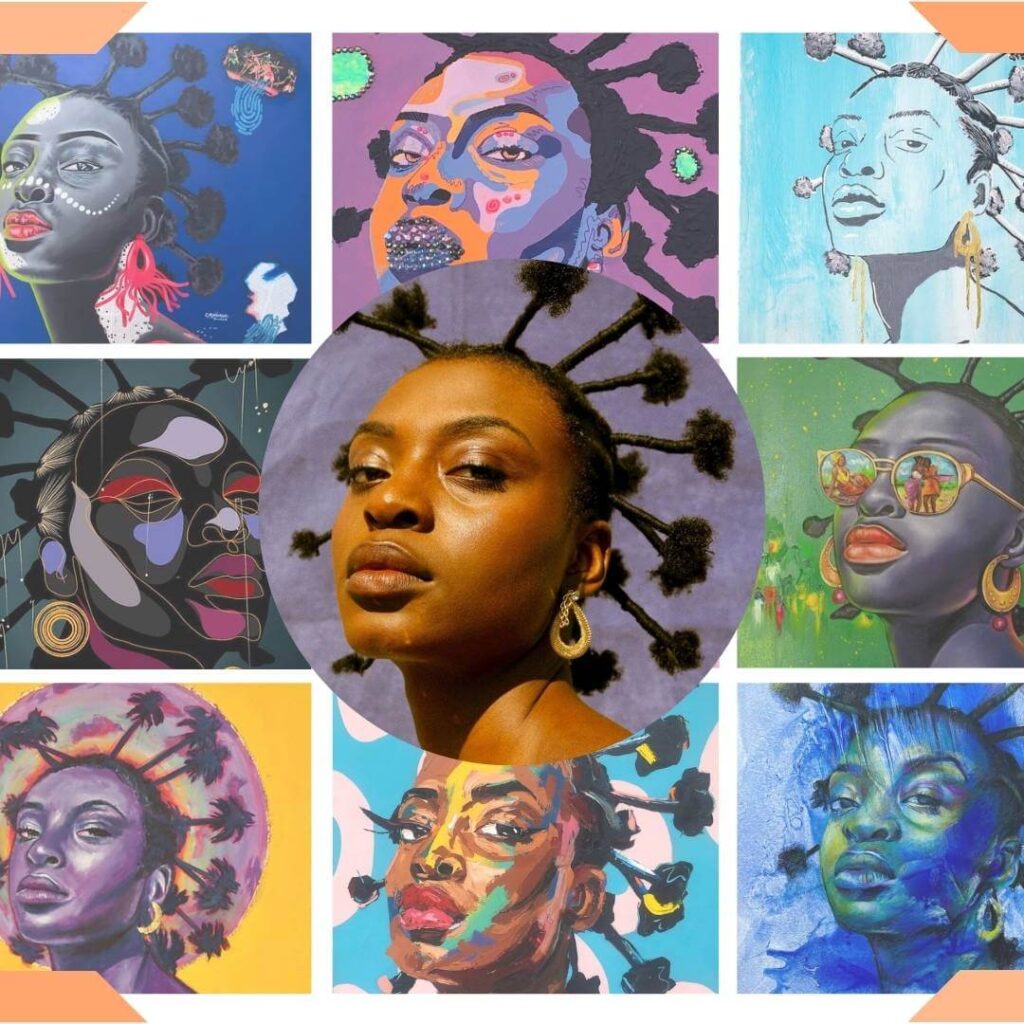

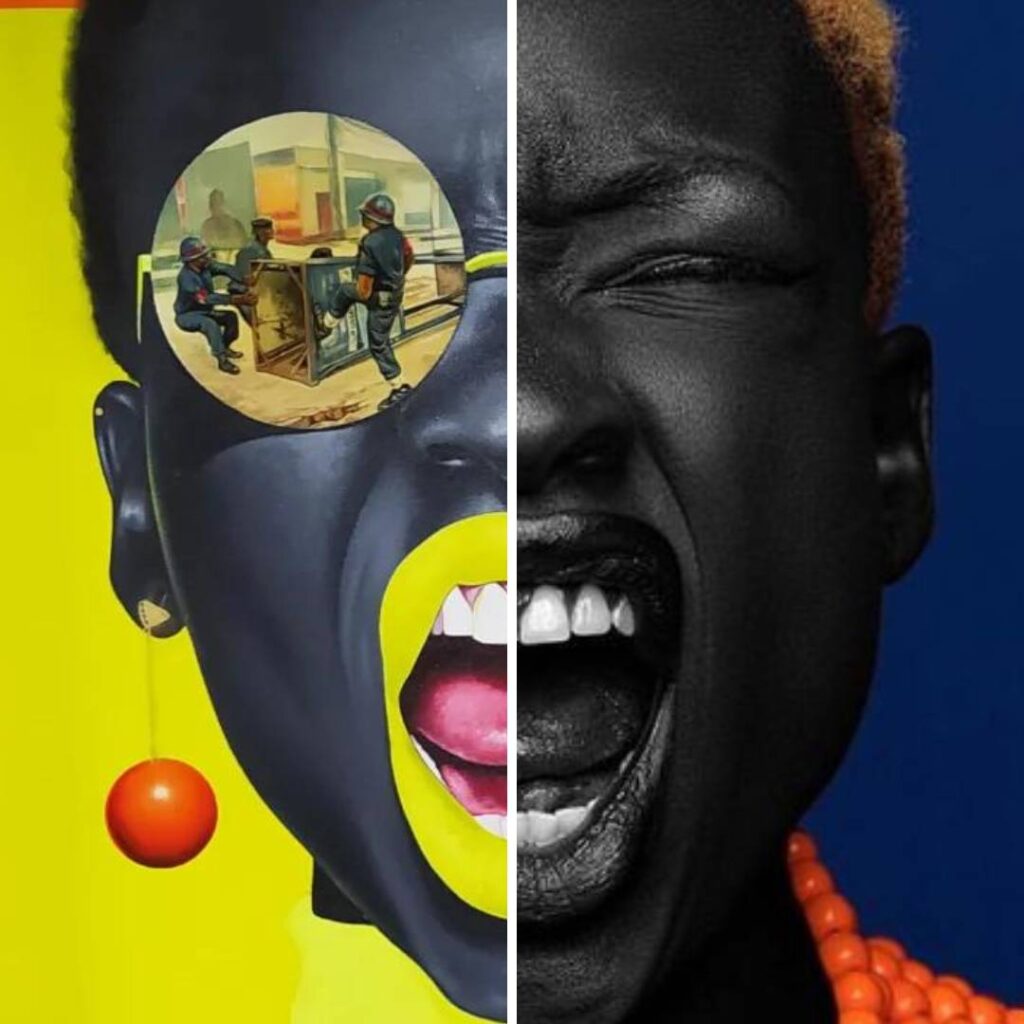

To investigate this, I conducted a simple experiment using Google Image Search. I took several paintings of African women that are widely available on the market, digitally removed the added colors and patterns that often disguise their origin, and reverse-searched the underlying image.

The findings were startling. The images I tested were not just “inspired by” photographs; they were perfect, 1-to-1 replicas. The evidence is presented in the collages below: on the left is the artwork being sold, and on the right is the original image found on Pinterest, separated by a white line.

Whenever an artist was identified with one copied image, a review of their portfolio almost always revealed they were a serial plagiarist. Some of these artists have achieved significant fame and exhibit their plagiarized works in well-known galleries abroad, demonstrating how the system fails to police itself.

When I asked a respected artist how these copyists achieve such photographic precision using only their eyes, he laughed. “Of course they didn’t do it like that,” he said. “They used a projection or even printed the image directly onto the canvas before painting over it.”

This isn’t art; it’s a technical forgery. The truly sad story is that these mechanically reproduced canvases are then sold for thousands of dollars to unsuspecting buyers who believe they are purchasing a unique, handcrafted original.

This article showcases only a small example, but the problem is vast. And the methods are evolving, though the intent to deceive remains the same. I was recently contacted by an artist I had previously exposed as a serial plagiarist. He presented his “new work” to me, indirectly positioning himself as a changed man who had moved on from his fraudulent ways. The reality was far more cynical: his new portfolio was entirely generated by AI. Furthermore, he wasn’t just showing it to me; he was actively trying to sell these AI outputs, attempting to use our platform to legitimize his latest scheme. This proves a chilling point: those profiting from this system have no incentive to stop and return to the difficult work of original creation. They simply find new, more efficient ways to scam the market, moving from tracing to AI generation without a second thought.

The Conscious Collector: A Guide to Ethical Investment

Art consumers, particularly international collectors, hold immense power to reshape the African art market. Your choices directly determine which artistic practices thrive. It begins with understanding that purchasing stereotypical, plagiarized portraits isn’t a neutral act; it perpetuates a cycle of dehumanization and intellectual theft rooted in a colonial past. Furthermore, buying art is a significant financial investment. Opting for clichéd work often means paying inflated prices for pieces devoid of originality. These works are unlikely to appreciate and may plummet in value if the artist’s lack of authenticity is exposed. As one seasoned art collector advises, “In an era of instant information, be wary of investing in art that lacks originality or provenance.” True value lies in an artist’s unique vision, which offers both cultural depth and financial integrity.

Navigating this landscape requires a discerning eye. The simplest rule is to be highly skeptical of colorful portraits that rely solely on stereotypical African traits. However, the goal isn’t to abandon portraiture but to find the authentic practitioners within it. We encourage artists to find their models in real life, not online, to build a genuine connection that no stolen image can provide. For you, the collector, this translates into a few critical actions. First, scrutinize the artist’s entire portfolio. A collection filled with dozens of near-identical, exoticized faces is a major red flag. Second, always ask the gallery or artist two essential questions: “Who is the person in this picture?” and “Why did you choose to paint her specifically?” An authentic artist will have a story—a name, a moment, a reason. A plagiarist will deflect.

Finally, the integrity of the gallery is paramount. Understand that establishments exist that operate as fraud mills, scamming both their clients and their artists. This is why your most powerful question is one of accountability: “What is your policy if an artwork is later discovered to be plagiarized?” A reputable gallery will have a clear, written policy for a full refund, seeing it as a matter of honor. A complicit one will have no answer. Remember, even major institutions are not immune, as shown when a work by renowned Spanish artist Javier Calleja was removed from the MoMA Design Store after being exposed as a copy. The difference with a serious gallery is how they respond: they take responsibility. By asking these questions, you ensure your investment supports a vibrant, ethical, and authentic artistic future.

“In an era of instant information, be wary of investing in art that lacks originality or provenance.” – A seasoned Art Collector

Conclusion: Championing Authenticity

The cycle of exoticizing and plagiarizing portraits of African women is a systemic issue, rooted in a colonial past and sustained by a modern market prioritizing profit over integrity. The evidence is clear: from traced photographs to AI-generated fraud, this practice dehumanizes its subjects and scams unsuspecting buyers.

Yet, this is not the true story of African portraiture. Look to Ben Enwonwu’s Tutu, a portrait of Princess Adetutu Ademiluyi. It stands as a powerful counterpoint; a masterpiece of specific, dignified representation. Born from collaboration and artistic genius, not theft.

But as this system has been built by choices, it can be dismantled by them. The responsibility does not lie with struggling artists to resist market pressures alone. It lies squarely with galleries to uphold rigorous ethical standards and, most importantly, with us; the consumers.

Your power as a collector is immense. Every purchase is a vote for the kind of art world you want to exist. You can choose to invest in clichéd frauds that devalue cultural heritage, or you can choose to champion genuine creativity.

Choose to ask, “Who is this woman?” Choose to scrutinize portfolios. Choose to demand a gallery’s plagiarism policy. Choose to support artists who find their models in the real world, whose work tells a story deeper than a trending color palette. Choose to seek out platforms that value transparency and authenticity.

By making these conscious choices, we do more than just acquire a beautiful object. We become patrons of truth. We support artists in building sustainable careers based on original expression, not forgery. We help preserve the rich, diverse, and authentic narratives of African art for future generations. And we finally break the centuries-old cycle of reducing African women from subjects of curiosity to subjects of art.

Comments