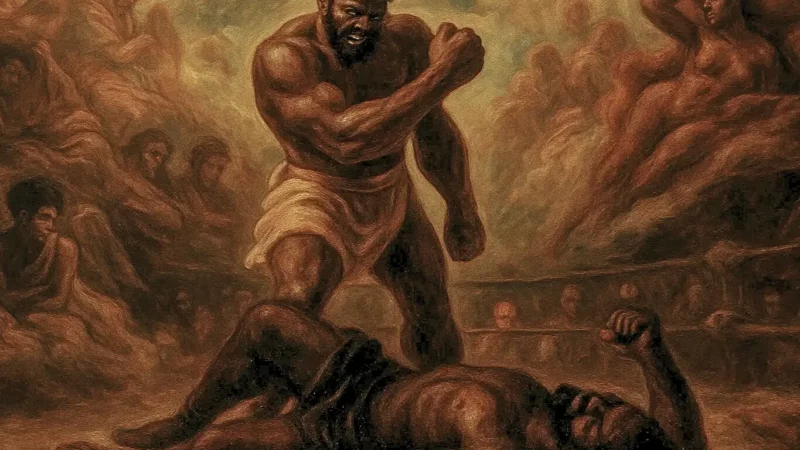

Neither Jungle Nor Rumble: Clash of Two Titans on Sacred Ancestral Ground

History remembers the moment the titans clashed, but it forgets how two warriors were transformed into those titans. That story was written during the five-week delay that stranded them in Kinshasa. The city itself was a crucible, forging each man into his mythic role. One became a titan by dissolving into the world around him, drawing strength from its soil and people. The other was hammered into an opposing titan by his solitude, his power hardening in the silence, fueled by alienation and a longing for home.

And that is how myths are forged. In the unseen struggles. Long before the first bell.