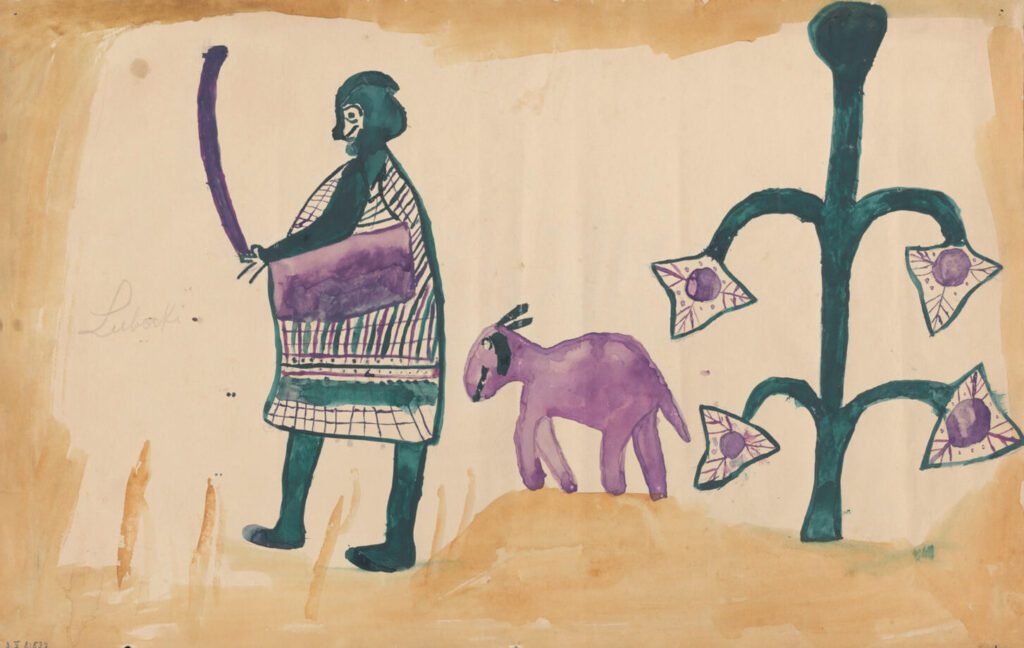

As the first female Congolese painter to achieve international recognition, Antoinette Lubaki left an indelible mark in art history. Born in 1895 in Bukama, a village in the Haut-Lomami province of what was then the Belgian Congo, she transcended both colonial and gender barriers, creating art that would eventually captivate audiences across continents. Her paintings, rich with scenes of daily life, folklore, and the natural landscape, offer a remarkable window into Congolese culture and traditions. Yet despite her work’s international acclaim, her full story remains largely untold.

Antoinette’s artistic career was closely linked to the colonial context that shaped her life and work. While her talent was extraordinary, the Belgian colonial system severely constrained her opportunities. She worked under oppressive conditions, receiving meager weekly wages for a mandated quota of artwork while being denied control over her own creations. Her artistic career, spanning merely five years, embodied the harsh realities of colonial rule. It began with her discovery by one Belgian officer and ended abruptly when another decided to suppress her work. A stark illustration of how colonial power could arbitrarily grant and withdraw artistic freedom.

Roots in Tradition: The Early Years

Antoinette Mfimbi grew up in Kabinda, surrounded by the artistic traditions of the Luba people. As the daughter of a village chief, she learned mural painting from her mother, using natural pigments from ochre, charcoal, and plant dyes to transform village houses into living canvases.

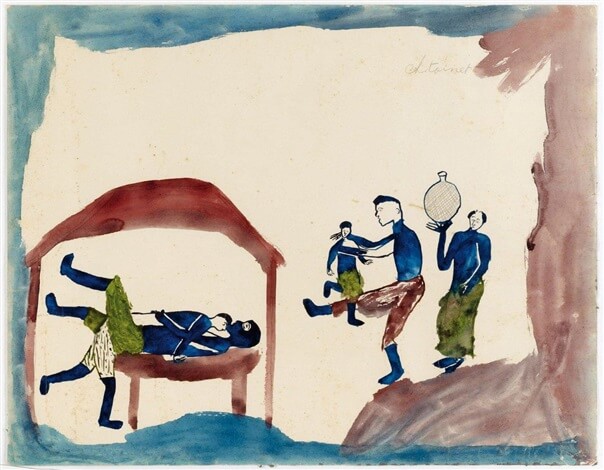

Her early works depicted scenes of childbirth, harvest celebrations, and ancestral spirits. She painted at night by candlelight, following the Congolese tradition that forbade telling legends before sunset. These subjects preserved communal memory and traditions threatened by colonial transformation. The flowing lines and rhythmic patterns that later attracted European audiences originated in these murals, where geometric designs mixed with figurative elements in a distinctly Luba style.

Creative Partnership: The Lubaki Collaboration

Antoinette’s marriage to Albert Lubaki, a master ivory carver, created one of Congo’s most significant artistic partnerships. Their collaboration crossed traditional boundaries between men’s and women’s artistic domains. Albert brought his expertise in bold, angular animal forms from ivory carving, while Antoinette contributed her mastery of human figures and narrative composition.

Together, they expanded Luba art to include the colonial world. Their murals featured automobiles alongside antelope, railway lines crossing ancestral pathways, and rifles in hunting scenes that once showed only spears. This wasn’t simple documentation but sophisticated commentary on two worlds that refused easy categorization.

Their joint works appeared in both private homes and public spaces, turning villages into galleries that recorded celebrations and upheavals. Each mural beautified spaces, preserved history, and subtly resisted colonial narratives that portrayed African culture as primitive.

The Colonial Encounter: Discovery and Exploitation

In 1926, Georges Thiry, a Belgian administrator and self-taught photographer with Surrealist connections, discovered the Lubakis’ murals during his administrative work in Katanga. Unlike most colonial officials who dismissed African painting as decoration, Thiry’s exposure to Art Nouveau and Surrealism helped him recognize innovation beyond European frameworks.

Thiry provided watercolor paints and paper, materials that changed Congolese art. The shift from wall to paper transformed how African art could circulate and be sold. Antoinette adapted her mural techniques to watercolor, developing a style that kept the spontaneity of traditional painting while using the medium’s capacity for subtle gradation and transparency.

This opportunity concealed exploitation. The artists had to surrender ownership of their works, a colonial practice that kept African creators as laborers rather than owners of their creativity. They never knew their works were sold in Europe or at what price. Today, these watercolors can fetch thousands of euros, highlighting the extent of this historical theft. The materials came with production quotas, thematic restrictions, and separation of the artist from their art.

Systematic Erasure: The Périer Period

Gaston-Denys Périer, a Belgian Ministry of Colonies official who wrote as Ariel Mucanda, managed the promotion of the Lubakis’ work in Europe. He controlled over half the press coverage of African art in Belgium before 1950, shaping public perception. He organized exhibitions in Brussels (1929), Geneva (1930), and Paris (1931), but described the 63 watercolors at the Palais des Beaux-Arts as “imagery of the bush,” relegating them to ethnographic curiosity rather than fine art.

Périer turned patronage into exploitation, implementing rigid production schedules that reduced artistic creation to industrial output. The artists received small weekly wages for meeting quotas while Périer accumulated 163 pieces and the creators remained poor.

When Antoinette’s work gained recognition in European galleries, colonial authorities spread rumors that the sophisticated watercolors were actually by a European plagiarist, implying such refined artistry was beyond African capability. This defamation campaign was part of a broader colonial strategy of denying African cultural achievement.

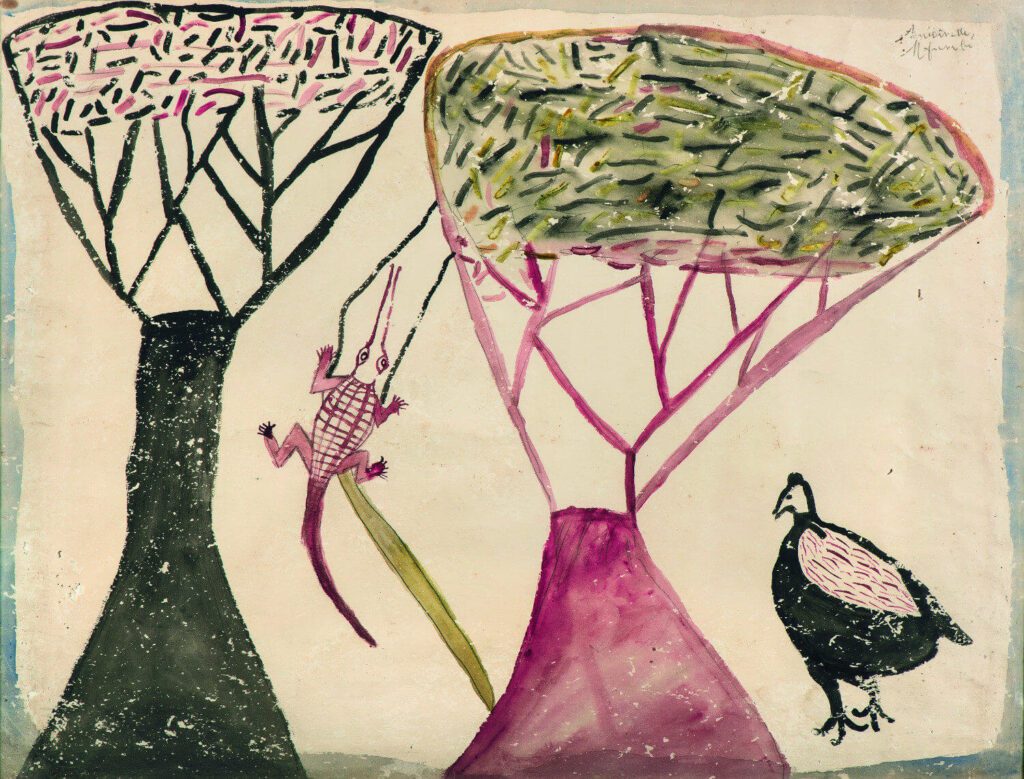

The gender discrimination becomes clear when compared to Tshyela Ntendu (Djilatendo), another Congolese artist whose works appeared in modern art galleries alongside Magritte and Delvaux, while the Lubakis remained in “Negro art” or ethnographic sections.

Périer’s writings erased Antoinette’s individual identity, using the shared initial ‘A’ of her and Albert’s names to present their distinct voices as one entity. In catalogs and reviews, her work disappeared into an “Lubaki” attribution that defaulted to masculine. When forced to acknowledge her, colonial commentators called her an assistant or copyist, never an artist.

Artistic Innovation: A Visual Language of Resistance

Despite constraints, Antoinette’s work showed remarkable innovation and subtle resistance. Her watercolors used indigo, a color with spiritual significance in Luba culture, to explore the psychological landscape of colonial encounter. Figures in her paintings appeared suspended between two worlds, their traditional dress mixed with colonial additions that seemed both decorative and constraining.

Her technique mixed perspective systems, combining the flat style of traditional murals with moments of three-dimensionality. Animals and humans occupied the same plane, refusing the nature/culture divide central to colonial ideology. Her pink and black crocodiles and unexpected tree colors weren’t naive choices but radical freedoms that challenged European expectations of “realistic” representation. Her use of negative space, leaving vast areas untouched, created incompleteness that invited contemplation.

Her themes went beyond documentation. Women pounding manioc became meditations on labor and tradition. Colonial officials appeared subtly caricatured, their rigid postures contrasting with fluid Congolese figures. Railways and roads carved through her compositions like scars, suggesting violence beneath progress.

The Silencing: End of an Era

In the early 1930s, a violent conflict between Thiry and Périer over control of the “primitive art” market resulted in withdrawal of artistic supplies from the Lubakis. This ended not just patronage but represented cultural violence. The support network that had allowed them to produce collapsed. By the late 1930s, Albert Lubaki reportedly lacked everything needed to work. After five years of prolific creation, during which she developed a unique visual language and gained international recognition, Antoinette was forced into silence.

The European art market yielded only two sales despite prestigious exhibitions, reflecting the period’s inability to value African painting beyond ethnographic interest. Without materials or market access, Antoinette disappeared from the artistic record. The date and circumstances of her death remain unknown, a final erasure showing how thoroughly colonial systems could disappear those they had showcased.

Rediscovery and Revaluation: A Contemporary Renaissance

The 21st century has seen gradual restoration of Antoinette Lubaki’s place in art history. In 2012, the Fondation Cartier in Paris included her work in “Histoires de Voir,” though initially listing pieces under Albert’s name alone. This error was corrected in the 2015 exhibition “Beauté Congo 1926-2015 Congo Kitoko,” curated by André Magnin.

The 2022 Venice Biennale presented Antoinette’s work as foundational to understanding global modernism, not as ethnographic curiosity. Contemporary efforts include the AWARE database (Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions), which creates biographical notices to restore visibility to erased women artists, and galleries like Magnin-A in Paris that represent her remaining work: approximately 60 to 70 cataloged watercolors, fragments of likely more abundant production.

Scholars now recognize how her synthesis of traditional and modern elements anticipated postcolonial art concerns. Her treatment of hybridity, critique of colonial power, and maintenance of indigenous aesthetic systems while using European materials offer insights into artistic resistance and adaptation.

Museums have begun reattributing works previously assigned to “A. Lubaki” or Albert alone, using stylistic analysis and documentation to restore Antoinette’s authorship. This process represents broader reckoning with how colonial and patriarchal systems shaped art historical narratives.

Legacy: Beyond Recovery

Antoinette Lubaki’s significance illuminates patterns of creativity and constraint in colonial Africa. Her story reveals how African artists found spaces for innovation within limiting structures. The evolution from mural to watercolor, from communal to commodified art, traces the transformation of African cultural production under colonialism.

Her work challenges stereotypes about “traditional” versus “modern” African art. The commentary in her paintings shows that African artists were active interpreters and critics of historical change, not passive recipients of colonial modernity. A leopard’s spots might echo a colonial administrator’s tie pattern, or a railway line disrupts a village scene’s circular composition.

For contemporary artists, particularly African women creators, Antoinette provides both inspiration and warning. Her talent secured international recognition, yet the structures enabling that recognition destroyed her career. Her story demands questioning how narratives are constructed and whose voices they privilege.

Conclusion: An Unfinished Conversation

Antoinette Lubaki’s journey from painting murals in Kabinda to exhibiting in Paris to disappearing into silence embodies the dynamics of African art under colonialism. Her work testifies to the creative resilience of African artists maintaining cultural continuity while engaging with change. It also reveals the violence in colonial “appreciation,” which celebrated African creativity while denying creators control over their production.

Recovery of her legacy represents more than historical correction. It’s an active process of decolonizing art history. Each reattributed painting, each article centering her voice, each exhibition presenting her as artist rather than artifact contributes to restoring not just Antoinette Lubaki but countless other African women artists erased by colonial systems.

As we uncover and celebrate her contributions, we must acknowledge what has been lost: the paintings destroyed or disappeared, the artistic development cut short, the voice silenced before fully articulating its vision. Antoinette Lubaki’s legacy lives in surviving watercolors and in questions her story raises about value, recognition, and the right to create on one’s own terms.

She painted by candlelight in colonial Katanga, creating worlds that darkness couldn’t extinguish. Her art continues speaking across decades, offering beauty and critique equally. In recognizing Antoinette Lubaki, we glimpse the richness of African artistic traditions and the cost of their suppression. Her story, still being written through each discovery and reinterpretation, reminds us that decolonization is an ongoing project requiring us to see not just what was created despite oppression, but to imagine what might have been created in freedom.

Comments