One November afternoon in 1979, in a modest home in Lubumbashi’s Cité KDL neighborhood, anthropologist Johannes Fabian sat down with Pilipili Mulongoy—an artist whose influence on modern African art is both pioneering and profound. At 65, speaking in Swahili, Pilipili shared his extraordinary journey from a humble plumber to a trailblazer in contemporary art. Based on one of the rare interviews ever recorded with him, this account goes beyond the usual biographical sketches to reveal the man behind the art in his own words.

From Village Drums to Urban Art

“I hadn’t done anything artistic—I didn’t even know how to draw,” Pilipili recalled, his tone unassuming yet determined as he revisited his life before art. Born in 1914 in Ankoro, Belgian Congo, he grew up in a world where creativity served practical and communal purposes. His father, a master drummer, crafted and played ceremonial drums that communicated messages between villages. “He would beat the drum here and talk to some village there,” Pilipili explained, likening these wooden instruments to a primitive telephone that united communities.

n 1944, amid strict colonial restrictions on movement, Pilipili embarked on an arduous journey away from his home. “The Belgian administration made trouble for me,” he said with a hint of pride. “They said there were no roads—no way, I said, I have to go.” Traveling by truck and mail boat, he eventually reached Élisabethville (now Lubumbashi), where his life was about to change in ways he never imagined.

The Art of Seeing

Three years later, fate intervened when Pilipili Mulongoy met Pierre Romain-Desfossés, a French veteran who had established an art workshop in the city. Desfossés challenged him with a simple test: draw a small wooden figure of a statue beating a drum. “I just knew how to do it when I looked at that little muzimu,” Pilipili recounted, his eyes lighting up with the memory. “I examined the statue until I knew exactly what it looked like, then I drew it.”

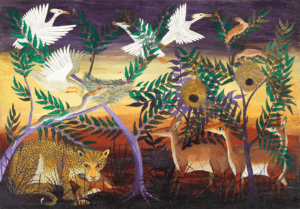

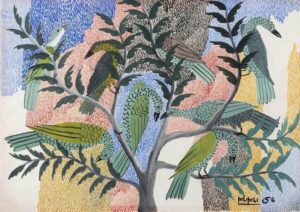

That keen eye for detail became his signature. Under Desfossés’ mentorship at the Hangar Workshop, Pilipili spent six years honing his distinctive style. He pioneered a unique pointillist technique he called “petit point,” crafting intricate patterns that transformed his depictions of nature into living, breathing landscapes. “Everyone should have his distinctive manner,” he asserted, echoing Desfossés’ belief that every artist must develop their own visual language.

The Artist’s Mind

What makes this conversation with Fabian so compelling is Pilipili’s reflection on the nature of artistic work. “The work of an artist is about thinking,” he insisted. “An artist keeps thinking all the time—even when asleep, even while taking a walk.” He drew a vivid parallel between artists and scholars, emphasizing that creative work is as much an intellectual pursuit as it is a form of expression.

When Fabian inquired about the vivid wildlife in his paintings—curious, given his long years in urban Lubumbashi—Pilipili’s answer was both simple and profound. “I picked up everything in my head. Having seen it in the past, I now recall everything there.” His art wasn’t created from immediate observation but from a deep, enduring reservoir of memory and imagination.

Legacy of Innovation

Pilipili’s talent quickly transcended local borders. In 1955, he won first prize in a Vatican-sponsored competition for religious art, with his “Way of the Cross” series receiving papal blessing. Collectors included members of the Belgian royal family, among them Kings Baudouin and Albert II.

After Desfossés’ passing, Pilipili played a crucial role in founding the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Lubumbashi. “I was the one who made the beginning here,” he recalled with evident pride. The academy soon became a model for art schools across the Congo, nurturing a new generation of artists and cementing his role as a visionary mentor.

Pilipili Mulongoy passed away in 2007 at the age of 93, but this rare interview with Fabian reveals more than a biography—it captures a pivotal moment in African art history. It is a story of how traditional forms met modern expression, how personal memory and imagination bridged the gap between past and present, and how one man’s journey could help redefine the very concept of contemporary African art.

A Lasting Voice

That November afternoon in Lubumbashi, as Pilipili recounted his life’s journey, he couldn’t have known how resonant his words would be. “If your head is not steady,” he warned, “you may get sick and your thoughts may drive you crazy.” This reflection on the all-consuming nature of artistic creation speaks to his deep commitment—not merely to a profession but to a way of life.

On the relationship between traditional craftsmanship and modern artistry, Pilipili Mulongoy offered an insight that speaks volumes about his enduring influence: “Whatever they made, everything shows an ability to progress. Everyone makes progress with their ability, slowly… Because where do abilities come from? They come from the fathers, first, and from the ancestors. In the end, ability comes, keeps growing, and then it is on its way.”

This belief—that artistic creation is both an inherited gift and an evolving practice—perfectly encapsulates Pilipili’s journey. From a man who had never drawn before to a master capable of recreating entire ecosystems from memory; from a student in Desfossés’ workshop to the founder of Congo’s premier art academy, Pilipili embodied progress in its most profound form. His conversation with Fabian, preserved like one of his intricate paintings, continues to offer insights not only into the process of making art but into how artistic traditions grow, adapt, and flourish over time.

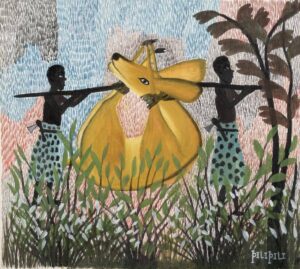

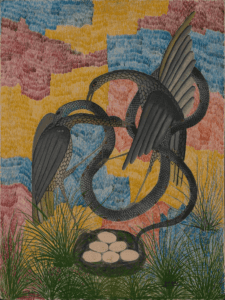

A Glimpse of His Art

If you’d like to view some of Mulongoy’s most iconic paintings, we’ve curated a small selection that highlights the breadth of his distinctive style. They are intended to give you a sense of his artistic range and skill.

However, if you are interested in acquiring a painting, his elder son has carefully preserved a separate collection of original pieces that are available upon request. For more details about these works or to discuss purchasing options, feel free to reach out at kitokongo.art@gmail.com.

I’ve also written a thought-provoking article on Le Hangar, titled The Illusion of Art: Le Hangar and the Colonial Propaganda, which delves into its role during the colonial era.

To delve deeper into the origins of this interview, you can consult the original transcript, translated, and annotated by Johannes Fabian. This additional resource provides further context and nuance to Mulongoy’s story, shining new light on his artistic philosophy and life experiences.

Comments

Hello, I am one of Pipipipi Mulongoy Granddaughter. I have an email to you with some photos of him and his family including my grandmother. I have been following and reading a lot about my grandfather since last year. My Family over here in America is very honoured to see his work and more. If you have any questions please let me know!