Introduction

History shouldn’t be reduced to a dry collection of dates and events. In the right hands, it can become a work of art, a story that speaks across time. This is exactly what Tshibumba Kanda Matulu (TKM) achieved in his remarkable paintings of Congo’s history.

At first glance, TKM’s paintings might appear simple. But look closer, and you’ll discover layers of meaning, hidden details, and powerful messages that can only be fully understood within their historical context. Through his brush, complex historical events are transformed into striking visual narratives that tell Congo’s story from a distinctly Congolese perspective.

In this first part of our journey, we’ve selected five paintings that chronicle the establishment of colonial power in Congo. We’ve paired TKM’s artistic vision with the historical events and context that inspired them, aiming to create something more engaging than a typical history lesson. This isn’t another Western lecture about Congo’s past – it’s a story told through Congolese eyes, painted by an artist who understood that history is more than just facts and dates.

Let’s begin our tour with Stanley’s arrival – the moment that would set in motion decades of colonial domination.

Stanley’s Arrival: Opening the Door to Colonization

Before Leopold II set his sights on Congo, Henry Morton Stanley had already made a name for himself in Africa. As a journalist for the New York Herald, he had achieved fame by finding the missing Scottish missionary David Livingstone in 1871, greeting him with the now-famous words “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” But Stanley’s return to Congo in 1876 had a very different purpose – he was now employed by Belgium’s King Leopold II, who harbored ambitious plans for the region.

Though presented to the world as a philanthropic and scientific mission, Stanley’s real task was to claim the Congo Basin for Leopold’s personal benefit. What followed was not exploration but the beginning of exploitation, setting in motion decades of colonial rule.

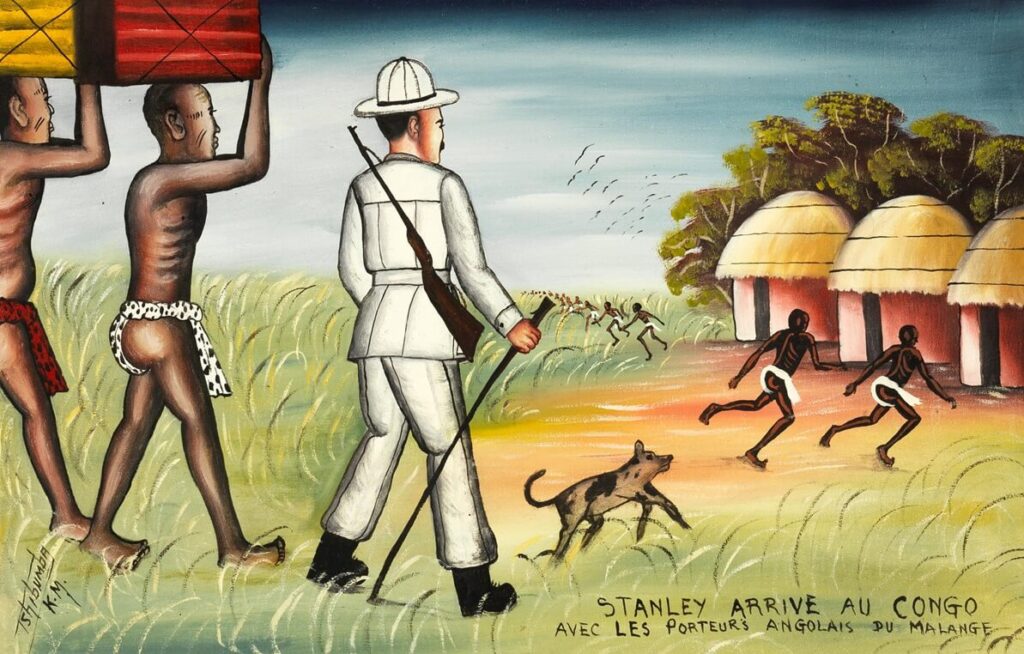

TKM’s striking painting “STANLEY ARRIVE AU CONGO AVEC LES PORTEURS ANGOLAIS DU MALANGE” captures this pivotal moment. Stanley strides confidently in his characteristic white colonial dress, rifle slung over his shoulder, while his hunting dog pursues two fleeing villagers – a chilling detail that transforms this supposed “exploration” into a hunting scene, with Congolese people cast as prey. Behind him, Angolan porters bend under the weight of heavy loads colored in the red, yellow, and black of the Belgian flag, symbolically carrying the weight of Belgian colonial ambitions into Congo. In the background, more villagers flee from their homes for their lives… Stanley the hunter has arrived.

Through TKM’s brush, we see this moment through Congolese eyes, where the arrival of European “civilization” appears not as progress, but as an ominous intrusion. The composition tells the story through carefully chosen details: the contrast between Stanley’s dominating presence and the barefoot porters, the fleeing villagers, and the traditional houses about to be forever changed. From this moment forward, no Congolese would ever feel truly secure in their own land.

The Death of King Banza Kongo: Betrayal After Victory

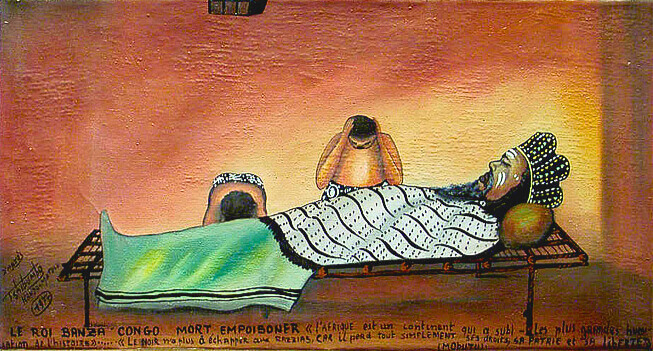

TKM’s somber painting captures a pivotal moment of colonial treachery. King Banza Kongo lies on a platform, his legs covered with a blanket and head resting on a pillow, his face covered with white clay (pemba) and adorned with a feather headdress (lusara wa nduba) – the symbols of his authority preserved even in death. His wife and a relative are present, with his wife hiding her face to conceal her tears, following the Congolese tradition that when a chief dies, all must remain silent in their mourning.

Below the scene, TKM inscribed words from Mobutu’s famous UN speech: “L’Afrique est un continent qui a subi les plus grandes humiliations… Car il perd tous simplement sa patrie et sa liberté” (Africa is a continent that has suffered the greatest humiliations… For it simply lost its homeland and its freedom). This quote, paired with the image of the poisoned king, connects the personal tragedy to the larger story of African dispossession.

King Banza had been a crucial ally to the Belgians in their war against the Arab-Swahili traders who controlled much of eastern Congo. The Belgians promised to make him king of Congo in return for his help. But once their mutual enemies were defeated, colonial authorities saw his growing influence as a threat. Their solution was ruthlessly simple – they organized a victory celebration and poisoned their ally’s food.

This betrayal marked a turning point in Belgian colonial strategy. They would no longer work through existing power structures but replace them entirely with their own administration. With Banza’s death, the pattern was set – any indigenous authority that might challenge colonial rule would be systematically eliminated. The path to complete colonial control was now clear.

The Congo Free State: Leopold’s Personal Colony

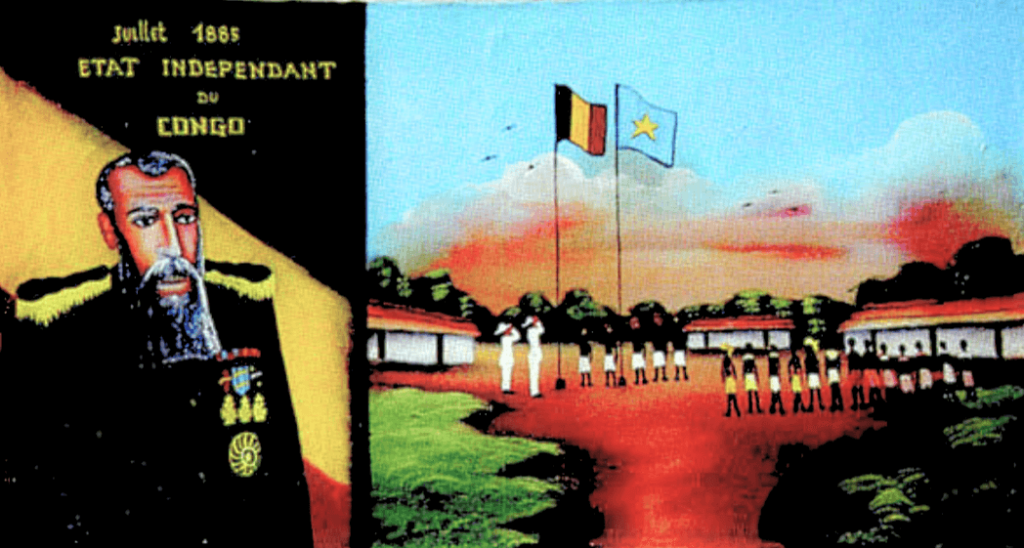

By 1885, after years of strategic maneuvering, Leopold II was ready to formalize his claim over Congo. His chosen name for this new possession contained a cruel irony. The “Independent State of Congo” seemed to promise liberation for Congolese hoping for freedom. Instead, “independent” merely meant the territory would be independent from Belgium itself, becoming Leopold II’s personal property.

TKM’s painting captures not only this deception but a striking reality of colonial power. In his composition, only two white figures oversee eighteen Congolese – a proportion that reflects the historical reality where a tiny minority controlled the vast majority. This control was maintained through a complex system of divide-and-rule tactics: recruiting local chiefs as intermediaries, turning ethnic groups against each other, and creating a class of African enforcers who would maintain order for their colonial masters.

The major powers of Europe, gathered at the Berlin Conference, recognized Leopold’s claim to the territory. Though he would never set foot on its soil, he presented his venture to the world as a “humanitarian” and “civilizing” mission. The reality would prove very different – the Congo Free State became a massive extraction operation, exploiting rubber, ivory, and minerals through forced labor and brutal repression.

Through this masterful manipulation of both language and local power structures – an “independent” state that was actually his private possession, controlled by a few through many – Leopold II had created a unique colonial entity that would allow him to rule Congo without any oversight from the Belgian parliament or public.

M’siri’s Head: The Final Conquest

While most of Congo had fallen under Leopold II’s control with the establishment of the Congo Free State, the mineral-rich region of Katanga remained stubbornly independent under its powerful ruler M’siri. Originally a trader from present-day Tanzania, M’siri had built his kingdom through cunning and brutality. After gaining the trust of Chief Katanga and forming an alliance with him, M’siri revealed his true ambitions – eliminating potential rivals, including the chief’s own son, to establish one of Central Africa’s most powerful kingdoms.

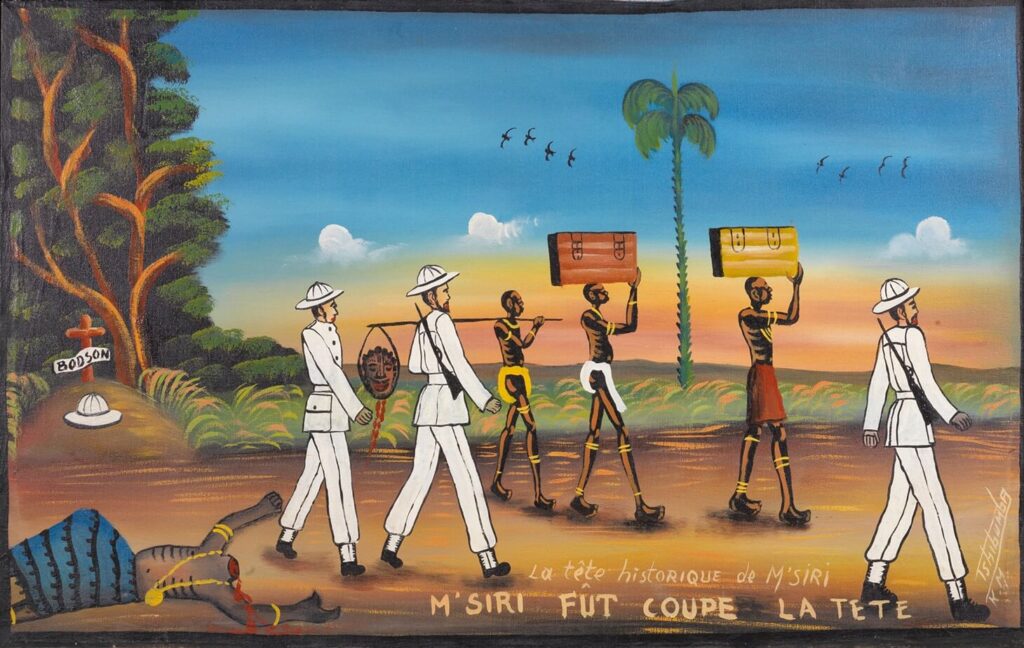

In 1891, Belgian colonial forces turned their attention to this last pocket of resistance. Captain Bodson arrived with Leopold II’s demands for submission. The confrontation turned deadly – Bodson shot M’siri, but M’siri’s men ensured their leader would not fall alone. Both men perished that day, but their deaths would be treated very differently.

TKM’s unsettling painting captures this brutal aftermath. M’siri’s decapitated body lies in the foreground, still dressed in his regal blue-striped garment and gold ornaments, while colonial officers and porters cart away his head. The composition reveals colonial double standards – Bodson receives a marked grave with a cross, while the African king is dismembered. Local oral tradition adds a supernatural twist – M’siri’s head carried a deadly curse, with each person who carried it mysteriously dying on the spot, only to be replaced by another who would meet the same fate. The head’s final destination remains unknown, with some wondering if it ended up in a European museum or even in Leopold II’s possession.

With M’siri’s death, the last independent kingdom in Congo fell under Belgian control. The process that began with Stanley’s arrival was now complete – from the poison that killed King Banza to the bullet that killed M’siri, colonial power had systematically eliminated all rival authorities.

Colonial Rule: Different Name, Same Machine (1885-1959)

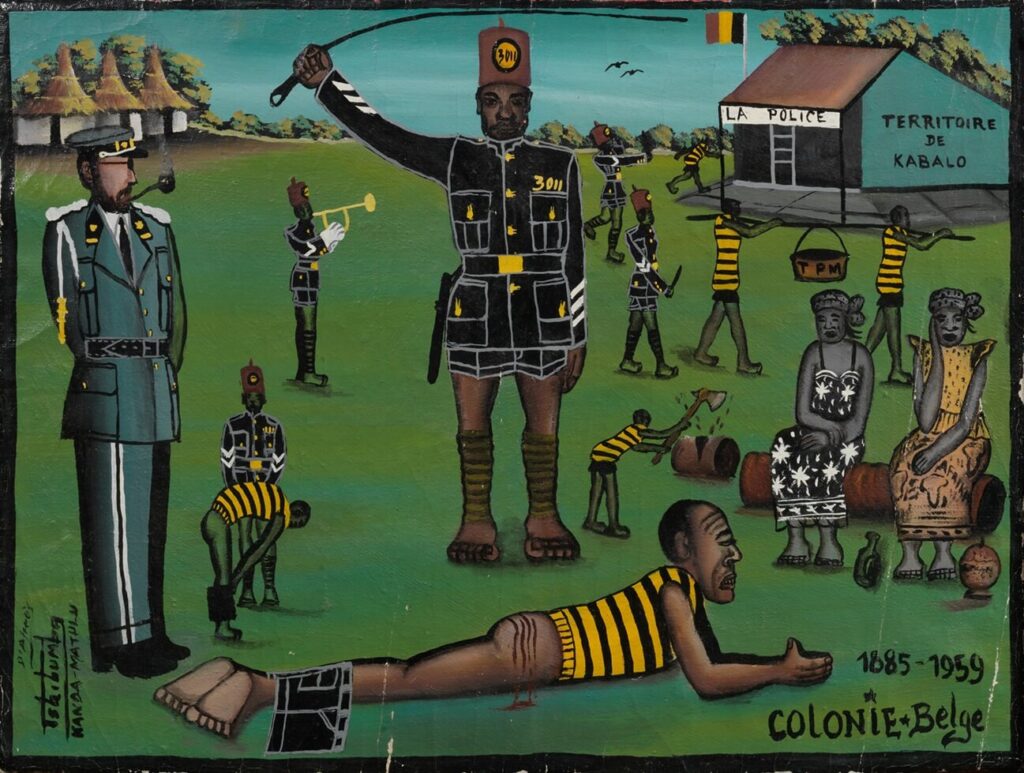

While 1908 marked Congo’s transition from Leopold II’s personal property to a Belgian colony – following international outcry over the Free State’s brutalities – TKM’s painting suggests this change meant little in the daily experience of Congolese people. Though the direct killing and severed hands that characterized Leopold’s rule diminished, the fundamental systems of exploitation, forced labor, and humiliation remained firmly in place.

TKM’s striking painting captures the essence of colonial control in the territory of Kabalo. A European officer in crisp uniform stands watching while African police officers, identifiable by their “3011” badge numbers – a system of control that allowed reporting of police abuse to superiors – enforce colonial authority with whips and batons. Tellingly, the building is marked only as “LA POLICE” – no prison is needed because under Belgian rule, the entire territory functioned as one large prison. Prisoners in striped clothing perform degrading tasks, including two men carrying a large bin marked “TPM” (Travaux publics ya mécanisation) containing waste. One manlies beaten on the ground while his wife watches helplessly, hand on cheek – a detail showing how public beatings were meant to humiliate not just the individual, but to punish entire families.

The scene illustrates how the colonial system operated through multiple layers of control and humiliation. The painting’s details tell the story: the whip-wielding officer, the morning roll calls where misunderstanding an order could result in a beating, and the Belgian flag flying over it all. The dates “1885-1959” frame this period of colonial control, with TKM deliberately blurring the distinction between Leopold’s personal rule and Belgian state control – for the Congolese, both meant systematic exploitation of their resources and their dignity.

Conclusion

We hope you’ve enjoyed this journey through the early chapters of Congo’s colonial history through TKM’s remarkable paintings – from Stanley’s arrival to the daily humiliations of colonial rule.

Yet these five paintings can only hint at the true horror of Leopold II’s Congo Free State. Over 20 million Congolese were killed, with countless more mutilated. Leopold’s forces demanded severed hands as proof of killings, often cutting them from living victims to save ammunition or to meet quotas. The brutality was so extreme that it shocked even other colonial powers, forcing the Belgian parliament to end their own king’s personal rule in 1908, transforming the “Congo Free State” into a Belgian colony.

While we could have included many more of TKM’s powerful paintings, we chose these five to keep our narrative focused. For those interested in exploring further, we highly recommend “Remembering the Present” by Johannes Fabian and TKM.

In Part 2, we’ll explore how this system of control began to crack, following Congo’s story through independence, Lumumba’s tragic fate, and the rise of Mobutu. Join us soon for the conclusion of this visual journey through one of Africa’s most complex histories.

Comments